“Life as a whole expresses itself as a force that is not to be contained within any one part. . . . The things we call the parts in every living being are so inseparable from the whole that they may be understood only in and with the whole.” ~Goethe

My 83-year-old father and I meet regularly at a quiet small-town eatery. Large windows light up the whole place. After my mother’s long illness and death he remarried, relaxing back into bird watching and church choir.

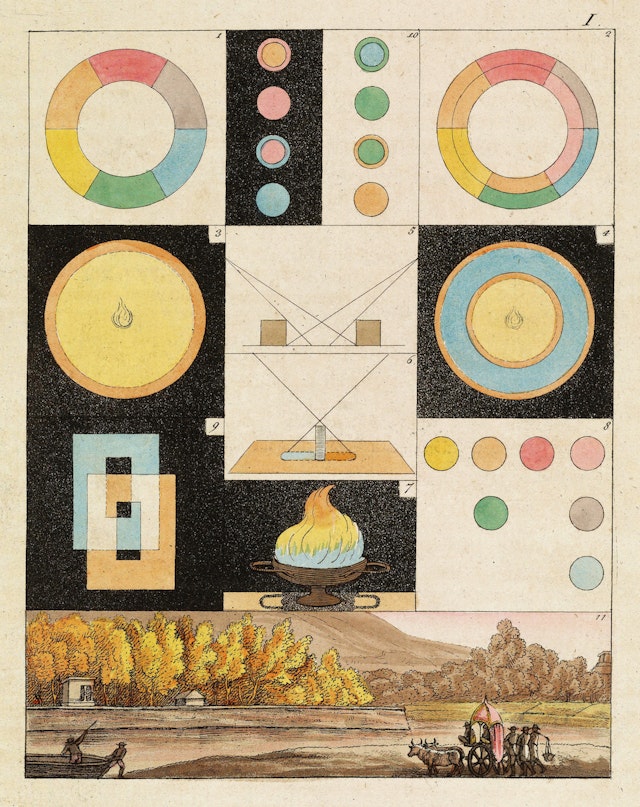

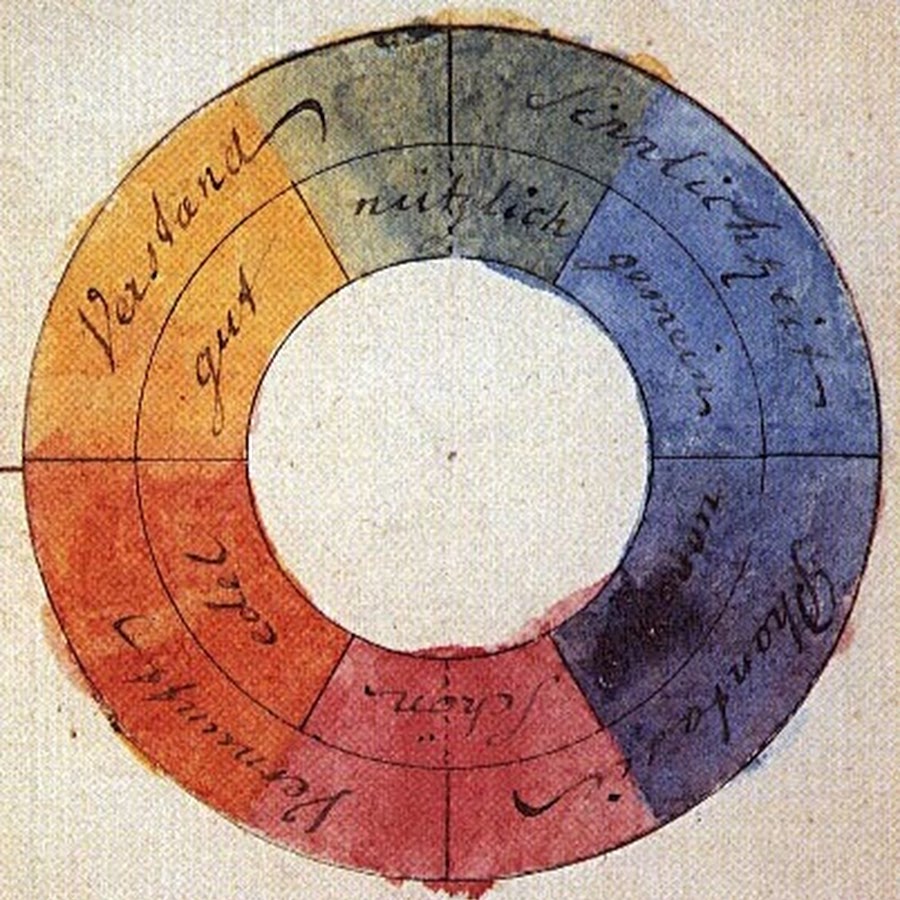

For years he made lists of things to talk about on the phone or in-person, an eccentric way to handle his shyness, but now we talk easily. While he eats a cherry pastry, I tell him about a biography of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe I’m reading. “Colors,” Goethe said, “are light’s suffering and joy.” He scoffed at critics who insisted he didn’t understand scientific theories about color and instead asserted that color required both darkness and light. Goethe believed personal observation was more vital than conventional knowledge.

My dad, a retired teacher, disagrees. He says theories must be mastered before making advancements. Goethe would have enjoyed debating that point. As we talk, beveled glass decorations at the windows break light into rainbows that bounce from my father’s face to the walls around him.

I’m grateful things have become close-friend comfortable between us. We talk and laugh companionably, happy to be sitting together rather than separated by the miles of our daily phone call. My father had been ratcheted tight by early adversity but something loosened in him recently.

In the past few weeks he’s begun telling me about his long-unspoken childhood. When my dad was five years old, his own father died after a short illness, leaving behind three small children and a wife with severe asthma.

Relatives told him he was now man of the family. One uncle took him hunting, even though my dad was barely big enough to carry the shotgun. My dad described that gun as a weapon lethal to anything in the direction it was pointed, including saplings. Occasionally, he managed to bring home squirrels for the family table. “But I would have rather had them for my friends,” he said. He described a rabbit he noticed in the yard every day after school. He wanted it to trust him enough to eat from his hand, but also felt the pressure to provide for the family. One day he killed it. Nearly 75 years later he said he still felt he’d betrayed that little creature.

He told me about his mother’s youngest brother, Uncle Arthur, whose every visit was “bad news.” Arthur would talk the young widow into lending him money, giving him her husband’s things, letting her little boy come work for him on day-long labors. He even talked her into handing over the award her husband had earned at work. “That Arthur was a scoundrel,” my father said, “but what a smart guy. He turned a Ford truck into a farm tractor. Never saw anything like it.”

Life insurance money paid out after their father’s death had been tucked safely away in the bank, only to be lost in the Depression’s bank failure. My dad described how his mother took her three children to the steps of the bank, wailing and banging on the front door. It remained locked. He told me about the day she sat her two older children down at the kitchen table and said she wasn’t sure how much longer she could feed them. She warned they might have to go to an orphanage. After that, he and his sister ate less and tried to prove in every possible way that they weren’t a burden. Their toddler brother, whose exuberance lifted the household mood, was too young to understand.

Most of our father/daughter conversations, however, were light-hearted and wide-ranging. On this morning we talk about books, music, science, and family news. After we visit close to two hours, my father says, “I’m sure you’re busy, I don’t want to keep you.” It’s his way of saying he still has a bike ride to go on, brain-training games to do, then dinner before choir practice. The sunny day holds no clue a new prescription is already weakening a malformed vessel inside his brain.

Before we hug goodbye he says, with uncharacteristic urgency, he has waited long enough for great-grandchildren. “There’s plenty of time,” I laugh, “your grandchildren are pretty young to think about having kids.”

A few nights later I have a long, intricate dream. In it I watch a strangely stylized battle between a man in medieval garb and various shadowy opponents amidst swirling greenish gray clouds. There may even have been a dragon. The fight goes on and on. The man struggles mightily, never giving up. I suffer for him. I can’t imagine he can bear much more. In a break from the action I see the object of these battles. It hangs on a decorated chain but, instead of an elaborate medallion or jeweled treasure, it looks like a laminated ID tag with unrecognizable symbols dangling from it.

Finally, the medieval man holds it up in exhausted victory. Startled, I realize the man who has been so wearily battling is a younger version of my father. He sees me, but looks intently beyond me. I turn.

There I see a long table filled with people I don’t recognize. Each one wears a different bright shade of monochrome clothing. No swirling clouds there, only brightness. These people are talking among themselves, completely ignoring the battle that just played out before them.

I address the group indignantly, annoyed they can chat so blithely despite the perilous drama that took place. “Haven’t you seen what just happened,” I sputter, waving my hand toward the scene of the recently concluded battle. Then the younger version of my father, still holding up the ID tag says, “They can’t see me. They’re my descendants.”

A few days later, my father dies.

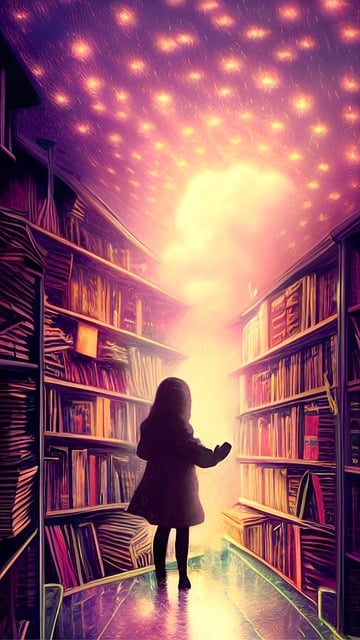

In my grief I turn back to Goethe. I flip through pages of his book, The Sorrows of Young Werther, immediately impatient with the author’s romanticized portrayal of death. I toss the unread book in a tote bag to return to the library, but miss. It sprawls open. As I pick it up, a single line stands out: “Life is the childhood of our immortality.” I have the sense, just for a moment, that I am a page in some greater book, only faintly aware of my place between those who have gone before me and those who will come after. I more gently place Goethe’s work in the bag, then let the rest of my day come.

This essay first appeared in the journal As It Ought To Be.

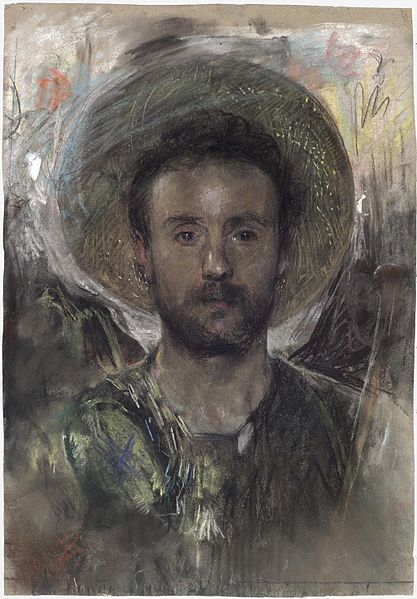

Illustrations from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s groundbreaking Zur Farbenlehre (Theory of Colours)