I hesitated at the heavy glass doors of my son’s school. I’d cheerfully walked in these doors many times. I volunteered here, served on the PTA board, joked with the principal and teachers, even helped start an annual all-school tradition called Art Day. But now I fought the urge to grab him from his first grade classroom, never to return.

I’d come in that morning hoping to discuss the angry outbursts my son’s teacher directed at several students, including my little boy. But I entered no ordinary meeting. It was an ambush. Sides had clearly been chosen. The principal, guidance counselor, and my son’s teacher sat in a clump together along one side of the table. Feeling oddly hollow, I pulled out a chair and sat down. Since I led conflict resolution workshops in my working life, I was confident that we could talk over any issues and come to an understanding.

I was wrong.

The counselor read aloud from a list of ADHD behavioral symptoms my son’s teacher had been tracking over the past few weeks. My little boy’s major transgressions were messy work, lack of organization, and distractibility. The teacher nodded with satisfaction and crossed her arms.

No one who spent time with him had ever mentioned ADHD before. I breathed deeply to calm myself. I knew it was best to repeat what I was hearing in order to clarify, but the counselor barreled ahead, saying they had a significant “ADHD population” in the school system who showed excellent results with medication.

After giving the teacher kudos for dealing with a classroom full of children and acknowledging the difficulty of meeting all their needs, I tried to stand up for my child (although I felt like a mother bear defending her cub from nicely dressed predators). I said the behaviors she noted actually seemed normal for a six-year-old boy, after all, children are in the process of maturing and are not naturally inclined to do paperwork. The teacher shook her head and whispered to the principal. The counselor said first grade children have had ample time to adapt to classroom standards.

I asked if any of my son’s behaviors had ever disrupted the class. The teacher didn’t answer the question. Instead she sighed and said, looking at the principal, “I’ve been teaching for 15 years. This doesn’t get better on its own. I’m telling you this child can be helped by medication.”

When I asked about alternatives such as modifying his diet the teacher actually rolled her eyes, saying, “Plenty of parents believe there are all sorts of things they can do on their own. But students on restricted diets don’t fit in too well in the lunchroom.”

There was no real discussion. No chance to bring up her teaching style. No opportunity for better collaboration between home and school. A conclusion had been reached without consulting me, my husband, or a mental health professional. My son required one vital ingredient in order to flourish in school: pharmaceuticals.

As I stood at the door, my heart pounding in distress, I vowed to solve this problem rationally. I told myself such an approach would help my child and other misunderstood students. I made it all the way to the car without crying.

Over the next few weeks I took my child to all sorts of appointments. A psychologist diagnosed him with ADHD (inattentive/distractible type) and said, after talking to me, that I probably had it as well. (It manifests somewhat differently in me.) Her report was tucked in a stack of handouts from a national non-profit organization known for its ties to the pharmaceutical industry. An allergist diagnosed our little boy with multiple food allergies including almost every fruit and grain he liked to eat (my research showed that diet can indeed affect behavior even for kids without allergies). A pediatric pulmonologist determined that his asthma was much worse than we’d known. In fact his oxygen intake was so poor the doctor said it was likely our son would change position frequently, lift his arms to expand his lungs, and have trouble concentrating. Right away I started the process of eliminating allergens in his life and following other advice given me by these professionals.

I also read about learning. I began to see childhood learning in a wider way as I studied authors such as Joseph Chilton Pearce , David Elkind

, David Elkind , James Hillman, and Bill Plotkin. I read about the gifts inherent in ADHD. I talked to other parents who described managing ADHD using star charts, privilege restriction, close communication with teachers, and immediate consequences for behavior. Many told me their child’s problems got worse during the teen years. Some described sons and daughters they’d “lost” to drug abuse, delinquency, chronic depression and dangerous rage. One woman told me her 14-year-old son was caught dealing. The boy sold amphetamines so strong they were regulated by the Controlled Substance Act—his own prescription for ADHD.

, James Hillman, and Bill Plotkin. I read about the gifts inherent in ADHD. I talked to other parents who described managing ADHD using star charts, privilege restriction, close communication with teachers, and immediate consequences for behavior. Many told me their child’s problems got worse during the teen years. Some described sons and daughters they’d “lost” to drug abuse, delinquency, chronic depression and dangerous rage. One woman told me her 14-year-old son was caught dealing. The boy sold amphetamines so strong they were regulated by the Controlled Substance Act—his own prescription for ADHD.

And I spent a lot of time observing my son’s behavior. Yes, he was disorganized with his schoolwork. His room was often a mess too, but only because he had so many interests. I saw no lack of focus as he drew designs for imaginary vehicles, pored over diagrams in adult reference books, or created elaborate make-believe scenarios. I knew that he was easily frustrated by flash cards and timed math tests, methods that did little to advance his understanding. But I also knew that he used math easily for projects such as designing his own models out of scrap wood. And of course he was distractible. He resisted rote tasks as most small children do. Their minds and bodies are naturally inclined toward more engaging ways to advance their natural gifts. Mostly I noticed how cooperative and cheerful he was. He didn’t whine, easily waited for his own turn, and loved to help with chores. As a biased observer I found him to be a marvelous six-year-old.

Resolutely I tried to make school workable. I let the teacher know how my son’s allergies and asthma might impact his classroom abilities. I shared the psychologist’s report. And I tried to explain my son’s stressful home situation. In the past year our family had been victimized by crime, his father had been injured in a car accident and left unable to work, and several other loved ones had been hospitalized. His schoolwork may have reflected a life that suddenly seemed messy and disorganized.

The teacher, however, only told me what my son did wrong. She was particularly incensed that he rushed through his work or left it incomplete, only to spend time cleaning up scraps from the floor. She did not find his efforts helpful. In clipped tones she said, “Each student is supposed to pick up only his or her scraps. Nothing more.”

My son’s backpack sagged each day with 10 or more preprinted and vaguely educational papers, all with fussy instructions. Cut out the flower on the dotted lines, cut two slits here, color the flower, cut and paste this face on the flower, insert the flower in the two slots, write three sentences about the flower using at least five words from the “st” list. I’d have been looking for scraps on the floor to clean up too, anything to get away from a day filled with such assignments.

It took almost two years of watching my child try to please his teachers and be himself in two different school systems that were, by necessity, not designed to handle individual differences. His schoolwork habits deteriorated except when the project at hand intrigued him. He appreciated the cheerful demeanor of his third grade teacher even though she told me she didn’t expect much from him until his Iowa Test results came back with overall scores at the 99th percentile. Then she deemed him an underachiever and pulled his desk next to hers, right in front of the whole class, to make sure he paid attention to his paperwork rather than look out the window or fiddle with odd and ends he’d found. That’s where he stayed, in the “not working up to your potential” morass common to many gifted kids.

When he was eight years old I took my children out of school forever.

Homeschooling didn’t “fix” everything for my son, at least right away. I made many of the same mistakes teachers made with him. I enthusiastically offered projects that meant nothing to him, expecting him to sit still and complete them. And I saw the same behaviors his teachers described. My son sat at the kitchen table, a few pages to finish before we headed off to the park or some other adventure. But every day he dropped his pencil so he could climb under the table after it, erased holes in his paper, found a focal spot out the window for his daydreams, complained as if math problems were mental thumbscrews. I used to lie awake at night afraid that he’d never be able to do long division.

Yet every time I stepped back, allowing him to pursue his own interests he picked up complicated concepts beautifully. I watched him design his own rockets. He figured out materials he needed, built them carefully and cheerfully started over with his own carefully considered improvements when he made mistakes. I realized his “problem” was my insistence he learn as I had done—from a static page. Homeschooling showed me that children don’t fare well as passive recipients of education. They want to take part in meaningful activities relevant to their own lives. They develop greater skills by building on their gifts, not focusing on abilities they lack.

The more I stepped back, the more I saw how much my son accomplished when fueled by his own curiosity. This little boy played chess, took apart broken appliances, carefully observed nature, helped on our farm, checked out piles of books at the library each week, memorized the names of historic aircraft and the scientific principles explaining flight, filled notebooks with cartoons and designs—-learning every moment.

Gradually I recognized that he learned in a complex, deeply focused and yes, apparently disorganized manner. It wasn’t the way I’d learned in school but it was the way he learned best. His whole life taught him in ways magnificently and perfectly structured to suit him and him alone. As I relaxed in our homeschooling life he flourished. Sometimes his intense interests fueled busy days. Sometimes it seemed he did very little— those were times that richer wells of understanding developed.

I sank back into worrying about academic topics during his last year at home before college. Although his homeschool years had been filled with a wealth of learning experiences I suddenly worried that he’d done too little writing, not enough math, minimal formal science. My anxiety about his success in college wasn’t helpful, but by then his confidence in himself wasn’t swayed.

His greatest surprise in college has been how disinterested his fellow students are in learning. Now in his sophomore year, my Renaissance man has knowledge and abilities spanning many fields. Of his own volition, he’s writing a scholarly article for a science publication (staying up late tonight to interview a researcher by phone in Chile). Self taught in acoustic design, he created an electronic component for amplifiers that he sells online. He also raises tarantulas, is restoring a vintage car, and plays the bagpipes. He’s still the wonderfully cooperative and cheerful boy I once knew, now with delightfully dry wit.

My son taught me that distractible, messy, disorganized children are perfectly suited to learn in their own way. It was my mistake keeping him in school as long as we did. I’m glad we finally walked away from those doors to enjoy free range learning.

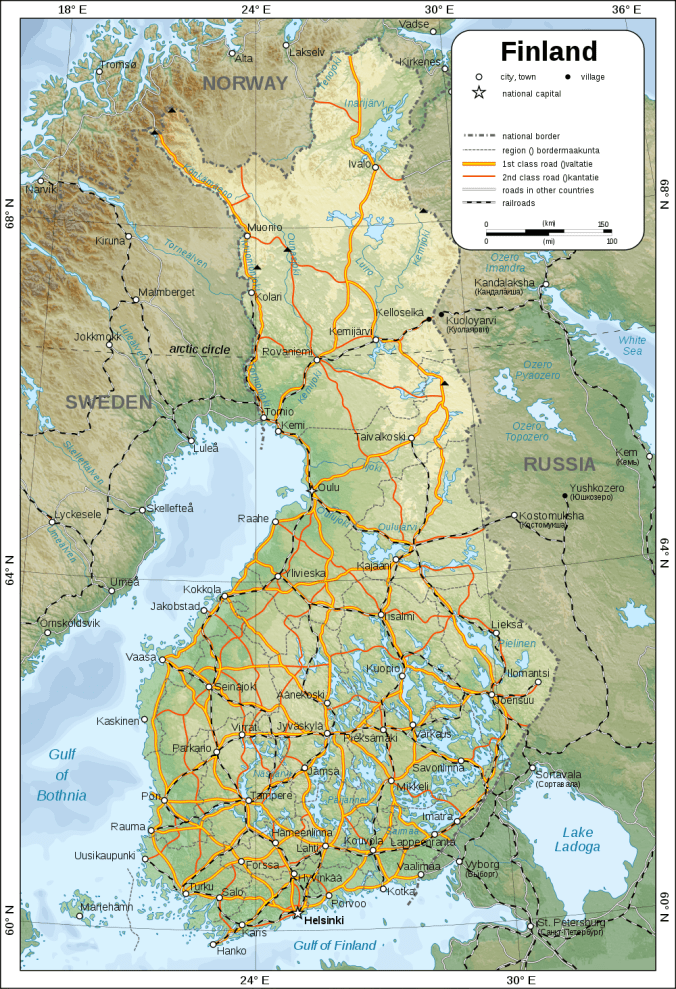

Wikimedia Commons

Find out more about Free Range Learning here.

by Warwick Cairns, “stranger danger” is so vastly overblown that you’d have to leave your child outside (statistically speaking) for about 500,000 years before he or she would be abducted by a stranger.

by resilience expert Michael Ungar. It can result in young people who are overly anxious or who take unnecessarily dangerous risks. It can also leave them unprepared for adulthood.