The teenaged years are actually the most rewarding of the homeschooling years. That’s what we’ve found with our four homeschooled children. And that’s what I was told by many of the 110 families I interviewed for my book Free Range Learning:: How Homeschooling Changes Everything . People in Ireland, Australia, India, Germany, and the U.S. described coming to this realization in similar ways. Their concerns about helping a young child master the basics or their struggles to find the right homeschooling style gradually resolved. Parents grew to trust the process of learning much more completely and, perhaps as a result, they saw their children mature into capable and self-directed young people.

. People in Ireland, Australia, India, Germany, and the U.S. described coming to this realization in similar ways. Their concerns about helping a young child master the basics or their struggles to find the right homeschooling style gradually resolved. Parents grew to trust the process of learning much more completely and, perhaps as a result, they saw their children mature into capable and self-directed young people.

Homeschooling isn’t the cure-all, by any means, for a culture that barely recognizes a young person’s need for identity and meaning. But homeschooled teens are not limited to the strictures of a same-aged peer culture or weighed down by a test-heavy form of education. They also have more time. This provides ample opportunity to stretch and explore in ways that can benefit them for life.

There are a number of pivotal elements in the period we call adolescence. Two significant ones are the pursuit of interests and meaningful work. These factors are just as important for teens in school as those who are homeschooling. But homeschoolers are freer to fill their time with what’s significant to them. That can make all the difference.

INTERESTS

Pursuing interests builds character traits that benefit us for life.

In my family, we’ve noticed that interest-based learning builds competence across a whole range of seemingly unrelated fields. For example, as a preteen one of my sons put together a few rubber-band powered airplanes at a picnic. When they broke, he tried fashioning the pieces into other workable flying machines. This got him interested in flight. He eagerly found out more through library books, documentaries, museum visits, and You Tube. Soon he was explaining Bernoulli’s principle to us, expounding on changing features of planes through the last century, and talking about the effect of flight on society. He designed increasingly sophisticated custom models. He read biographies of test pilots, inventors, and industrialists. He won a state award for one of his planes through 4H and got a family friend to take him for a ride in a small plane. What he picked up, largely on his own, advanced his understanding in fields including math, history, engineering, and physics. All inspired by learning that felt like fun.

This particular passion didn’t last, but the pursuit of his interests continued. He built spud guns with friends, played bagpipes in a highland band, bred tarantulas, repaired recording equipment, and tried his hand at woodworking. He wasn’t always at full tilt (never missing a chance to sleep in). Now a college student, he’s surprised that his fellow students are so turned off by learning.

Interests engaged him, as they do each one of us, in the pleasure of exploring and building our capabilities. They teach us to take risks, make mistakes, and persist despite disappointment as we work toward mastery. Making sure that a young person pursues interests for his or her own reasons, not the parent’s, keeps motivation alive and passion genuine. Research backs this up. Pursuing our interests builds character traits that benefit us for life.

Self-directed young people really take off in their teen years

Long-term homeschooling families know that self-directed young people really take off in their teen years. Comfortable with their ability to find out what they need to know, they often challenge themselves in their own ways. Some add ambitious schedules to previously unstructured days, others seek out heavy doses of academic work to meet their own goals, still others don’t appear to be remotely interested in conventional educational attainment but instead create new pathways for themselves.

Children as well as teens tend to have lengthy pauses between interests. A boy may not want to act in any more plays despite the promise he’s shown, a girl may not choose to sign up again for the fencing team just when she was starting to win most of her matches. During these slack times they are incorporating gains made in maturity and understanding before charging ahead, oftentimes toward totally new interests. The hiatus may be lengthy. They need time to process, daydream, create, and grow from within. They need to be bored and resolve their own boredom.

Children as well as teens tend to have lengthy pauses between interests. A boy may not want to act in any more plays despite the promise he’s shown, a girl may not choose to sign up again for the fencing team just when she was starting to win most of her matches. During these slack times they are incorporating gains made in maturity and understanding before charging ahead, oftentimes toward totally new interests. The hiatus may be lengthy. They need time to process, daydream, create, and grow from within. They need to be bored and resolve their own boredom.

Decades ago educational researcher Benjamin Bloom wondered how innate potential was best nurtured. He was convinced that test-based education wasn’t bringing out the best of each child’s ability. So he studied adults who were highly successful in areas such as mathematics, sports, neurology, and music. These adults, as well as people significant to them (teachers, family, and others), were interviewed to determine what factors led to such high levels of accomplishment. In nearly every case, it was found that as children, these successful people had been encouraged by their families to follow their own interests. Adults in their lives believed time invested in interests was time well spent. Due to their interests, these individuals developed a strong achievement ethic and a drive to learn for mastery.

This makes sense. We recognize that young people gain immeasurably as they pursue their interests. And not only in terms of success. When caring adults support a teen who loves to play baseball, study sea turtles, and draw comics, he’s likely to recognize, “I’m okay for who I am.” The interests well up from within him and are reinforced by those around him, so there’s coherence between his interior life and exterior persona. This reinforces a strong sense of self. All of us need sturdy selfhood to hold us in good stead while so many forces around us emphasize unhealthy and negative behaviors.

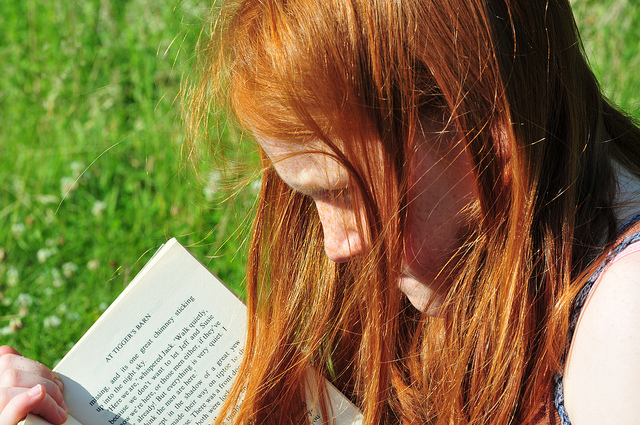

Interests have a great deal to do with promoting a young person’s feelings of worthiness. There’s an enhanced quality of life, a sense of being completely present that’s hard to name but recognized by those who “find” themselves within a compelling pursuit. A girl may love speed skating, or writing short stories, or designing websites. When she’s engaged in her interests, she knows herself to be profoundly alive. That feeling doesn’t go away, even when she has to deal with other tasks which are not as entrancing. Everyone needs to belong, contribute, and feel significant. The teen who knows his or her interests provide fulfillment is already aware that self-worth doesn’t come from popularity or possessions.

MEANINGFUL WORK

Teens want challenges and the accompanying responsibilities.

A group of homeschoolers touring a rural historical society noticed that storage areas were stuffed with uncataloged documents, some crumbling from age. They offered to digitally scan and reference these materials with the museum’s coordinator. Several other teens researched the requirements for a dog park in their suburb. Working with a group of interested citizens, they petitioned city council for a permit and eventually won a grant to construct the dog park. Another teen started a business fixing and modifying bicycles. He also earns revenue from videos of his mods. These examples from my book indicate how young people eagerly take on challenges and the accompanying responsibilities.

Throughout human history teens have fully participated in the work necessary to help their families and communities flourish. They were needed for their energy as well as their fresh perspective, and they built valuable skills in the process. Working alongside adults helped motivate them to become fully contributing adults themselves. Most of today’s young people are separated from this kind of meaningful work. They have fewer opportunities to encounter inspiring people of all ages who show them how to run a business or foster a strong community. Now that teens aren’t needed to run a farm or shop, they also don’t get as many real world lessons in taking initiative, practicing cooperation, deferring gratification, and working toward a goal.

Ideally young people have taken part in real work from an early age. Many studies bear out the wisdom of giving children responsibility starting in their earliest years. In fact, having consistent chores starting in early childhood is a predictive factor for adult stability.

Although work is largely valued for monetary reasons in our society, the kind of meaningful work I’m talking about has inherent worth. Chances are it is unpaid. (Here are dozens of service ideas for kids.)Through this work young people learn that it’s the attitude brought to any task, whether shoveling manure or performing a sonata, that elevates its meaning. Often an endeavor that’s inspiring doesn’t always feel like work. It may include establishing an informal apprenticeship, developing a small business, traveling independently, or volunteering with a non-profit.

It’s the attitude brought to any task that elevates its meaning.

What is meaningful work may be different for each person. A homeschooled teen may put up a shed for a neighbor, make a documentary with fellow parkour enthusiasts, perform puppet shows at a nearby daycare, help a zither club record their music, become a volunteer firefighter, assist an equine therapy program, coach a kids’ chess team, tend beehives, walk puppies at a dog shelter, or help a chemist in the lab. Through such work they tend to get more involved in their communities and connect with inspiring role models.

Meaningful work may not always be interesting, let alone fun. It has to do with putting in sustained effort to get results, even when the hours become long and the endeavor doesn’t feel rewarding. Through this work young people gain direct experience in making a valuable contribution. They know their efforts make a difference. That’s a powerfully rewarding experience at any age.

Learning of the highest value extends well beyond measurable dimension. It can’t be fit into any curriculum or evaluated by any test. It is activated by experiences which develop our humanity such as finding meaning, expressing moral courage, building lasting relationships, channeling anger into purposeful action, recognizing one’s place in nature, acting out of love. This leads to comprehension that includes and transcends knowledge. It teaches us to be our best selves.

Originally published in Lilipoh Magazine, Winter 2012