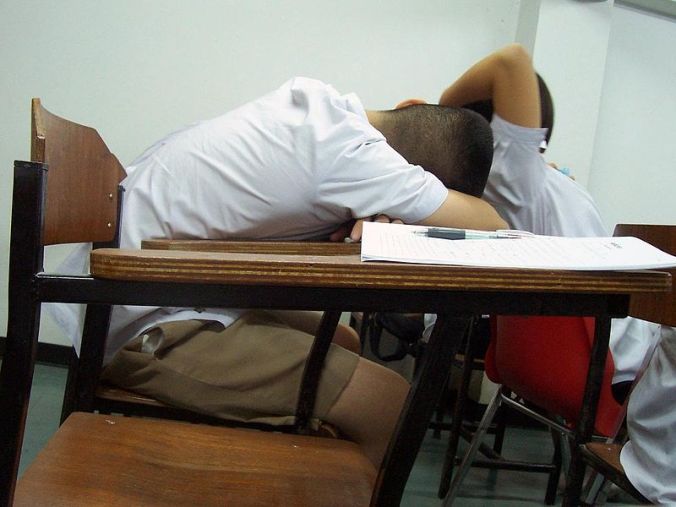

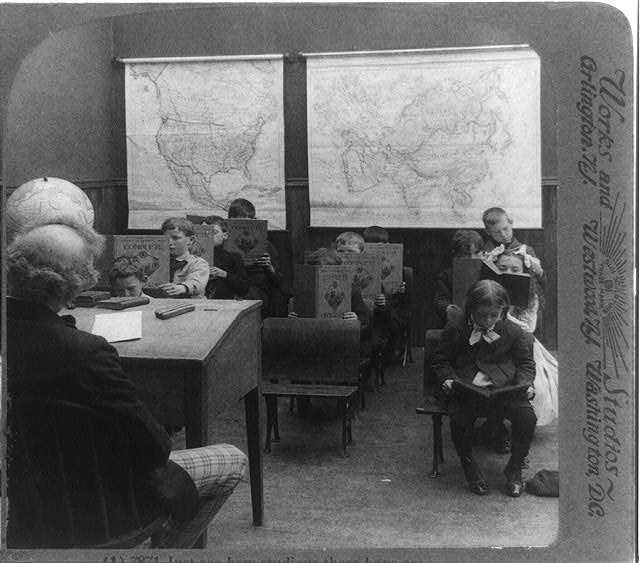

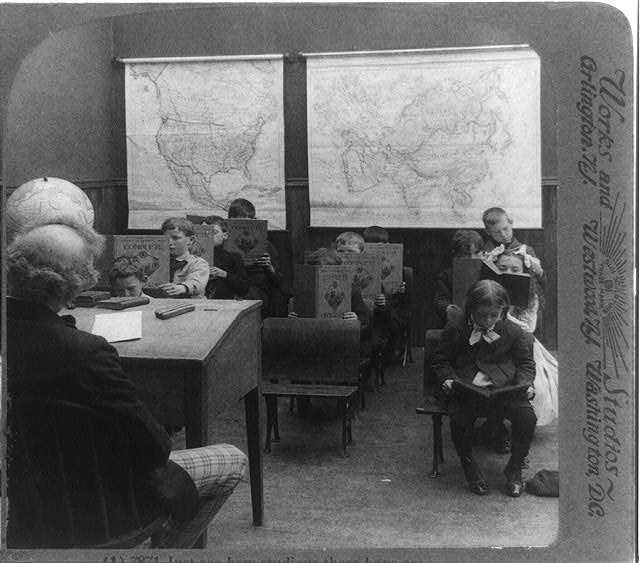

School in the old days may not have been ideal, but good teachers made all the difference. My father taught elementary school back when teachers had real options in the classroom. At least in his district, as long as his students generally covered the subject areas he was free to innovate. So he did. His fifth graders performed experiments, took care of the classroom snakes and rats, started school-based businesses, and perhaps most importantly, read and wrote about what they found interesting. Those days weren’t perfect by any means for students let alone teachers. But they’ve gotten worse. My father skedaddled out of the teaching business before standardized tests really hit education. But he saw the zombifying effect on schools, teachers and kids brought by high stakes testing.

Even in the best districts, attaining those all-important numbers eliminates opportunities for innovation and time to work with students’ interests. Those left behind see their schools under test-heavy siege charged with getting results or getting eliminated. This drive also shapes the kind of material students see, relentlessly preparing them to reach higher for the Almighty Score while giving scant attention to more complex yet essential skills for higher learning like critical thinking, creativity, initiative, and persistence.

Test Scores are not the Last Judgment

We might believe policy-makers know what they’re doing. Surely they haven’t been restructuring education based on bare numbers unless they had substantial proven results. Greater competiveness on the world market or at least greater individual success?

Nope.

Here are the actual results in this excerpt from Free Range Learning :

:

It’s widely assumed that national test score rankings are vitally important indicators of a country’s future. To improve those rankings, national core standards are imposed with more frequent assessments to determine student achievement (meaning more testing).

Do test scores actually make a difference to a nation’s future?

Results from international mathematics and science tests from a fifty-year period were compared to future economic competitiveness by those countries in a study by Christopher H. Tienken. Across all indicators he could find minimal evidence that students’ high test scores produce value for their countries. He concluded that higher student test scores were unrelated to any factors consistently predictive of a developed country’s growth and competitiveness.

In another such analysis, Keith Baker, a former researcher for the U.S. Department of Education, examined achievement studies across the world to see if they reflected the success of participating nations. Using numerous comparisons, including national wealth, degree of democracy, economic growth and even happiness, Baker found no association between test scores and the success of advanced countries. Merely average test scores were correlated with successful nations while top test scores were not. Baker explains, “In short, the higher a nation’s test score 40 years ago, the worse its economic performance . . .” He goes on to speculate whether testing [or forms of education emphasizing testing] itself may be damaging to a nation’s future

What about individual success?

In remarks to a Cato Institute Policy Forum, Alfie Kohn said, “Research has repeatedly classified kids on the basis of whether they tend to be deep or shallow thinkers, and, for elementary, middle, and high school students, a positive correlation has been found between shallow thinking and how well kids do on standardized tests. So an individual student’s high test scores are not usually a good sign.”

Why then do we push standardized tests if it has been shown that the results are counterproductive? Well, we’ve been told that this is the price children must pay in order to achieve success. This is profound evidence of societal shallow thinking, because the evidence doesn’t stack up.

Back in 1985, the research seeking to link academic success with later success was examined. It was appropriated titled “Do grades and tests predict adult accomplishment?”

The conclusion?

No.

The criteria for academic success isn’t a direct line to lifetime success. Studies show that grades and test scores do not necessarily correlate to later accomplishments in such areas as social leadership, the arts, or the sciences. Grades and tests only do a good job at predicting how well youth will do in subsequent academic grades and tests. They are not good predictors of success in real-life problem solving or career advancement.

For-Profit Charters are not the Promised Land

Now the much-touted documentary Waiting for Superman indicts today’s schools. The film hasn’t opened yet, but advance publicity makes it clear that solutions include whipping the teacher’s union into submission while tossing money at the problem. Waiting for Superman follows five families as they try to spare their kids the fate of bad public schools by enrolling them in promising charter and magnet schools. These are surely among the best charter and magnet schools in the country. But with our tendency to simplify any message, this film will surely be used to advance public perception of all charter schools. And that’s a very short-sighted approach.

Yes, there are some good ones, even some great ones out there. But let’s consider for a moment that many charter schools are run by for-profit companies. Making public education into an opportunity for entrepreneurs is not the solution. Owners have to make money somewhere. As a result they pay teachers very little, emphasize public relations, and provide little more than a rote McSchool education. Meanwhile they rake in stacks of taxpayer cash. Some charter schools provide nothing more than all-day computer based curricula for students to use at home (co-opting the term “homeschooling”) or in poorly run facilities. Unlike public schools, many charter schools can handpick their students, resulting in better overall test and behavioral outcomes. Even when children gain entrance by random pick, there’s an undeniably positive effect on students and their families who feel they’ve gained a leg up.

I’m not against entrepreneurs. I’d simply prefer to see them turn their attention to wind turbines and solar cells. My concerns are based on what’s happening in my home state. Here in Ohio, White Hat Management, owned by David Brennan, is the largest charter school operator in the state and the third-largest in the U.S. They may have the most dedicated teachers and support staff possible but management is out for the money. Currently 10 White Hat run schools are suing the company hoping to get out of contracts. Why?

An attorney for the charter schools comments, “White Hat Management is a for-profit company. Its interest in making a profit often conflicts with the schools’ goal to educate and show student progress. There are no real rules in place to make White Hat fully account for the nonprofit dollars they receive to manage Ohio charters.”

A Columbus Dispatch article noted Brennan was making nearly $1 million for each charter school his company operated.

It’s not as if charters are better. According to a Stanford University study, charter schools here in Ohio underperform compared to public schools.

That’s true across the nation as well.

Comparing data from 70 percent of all charter students in the country, attending one of 2,403 charter schools, it was found that these schools were no better and often worse than their public school counterparts. Comparing math achievement, charter students had gains in 17 percent of the cases. But charter schools had no impact in 46 percent and a negative impact in 37 percent.

We knew this back when President Bush enthusiastically promoted poorly ranked charter schools. Now we know, at least in the case of some for-profit ventures, the concerned voices of parents and community members aren’t likely to be heard beyond “press one for public relations.” They may, as in Ohio, have to sue to free themselves from money-changers right there in the temple of learning.

No Need to Wait, We’re the Super Heroes

The big changes in our society have come about as the result of ordinary people demanding accountability while making changes themselves. Everything from civil rights and environmental protections to natural childbirth—- our ideals, our struggle.

Waiting for Superman urges us to insist on similar changes in our schools. But change isn’t about throwing more money at the problem. It certainly isn’t about letting corporations get a stronger foothold in schools where BP writes science materials and advertising is ubiquitous.

The change highlighted in the film is spurred by concerned parents and amazing teachers like Jeffery Canada. I’m a big admirer of Canada’s work I read both his books Fist Stick Knife Gun: A Personal History of Violence in America and Reaching Up for Manhood: Transforming the Lives of Boys in America

and Reaching Up for Manhood: Transforming the Lives of Boys in America when they came out. The other teachers showcased in the film are equally creative, brilliant and caring.

when they came out. The other teachers showcased in the film are equally creative, brilliant and caring.

Do we see the irony here? This film showcases innovative teachers and child-centered programs, holding them up as the last hope to “save” kids from bad public schools. Exactly the sort of conditions that benefitted my father’s public school classroom before high stakes testing and business models got in the way.

There’s no “silver bullet.” We’re talking kids here, kids who start out with curiosity and eagerness. Sure, we can funnel a few lottery winners into trendy themed schools like Q2L or we can recognize that all children are born to learn in the way that best suits them, as they do in Democratic Schools.

While tests measure what kids have yet to achieve, kids themselves more naturally seek to engage in the wonderfully exciting work of mastery, guided by parents, teachers, grandparents, clergy, friends and the world around us. The strictures of school tend to limit learning, as I explain at length in my book which is one reason a few million of us homeschool, creating every day the kind of responsive and individualized education that best suits our children.

But that’s not workable for everyone. So let’s figure out what changes will really benefit our children and our communities.

1. Let’s find out about the holistic, uneven and delightfully unique ways that children learn.

2. Let’s look beyond trends, reading publications written by parents and teachers such as Education Revolution Magazine, Rethinking Schools, and Encounter: Education for Meaning and Social Justice.

3. Let’s pay attention to the thoughtful, experience-informed work of today’s unsung educational luminaries including Ron Miller, Jerry Mintz, Chris Mercogliano.

4. And perhaps most importantly, lets pay attention to what those who love to learn have to say. Our kids tell us how they learn best each day not only through their enthusiasm but also through their stubbornness, anger, despair and numbness. They need to participate in meaningful work, to apply real skills, to pursue their own interests, to advance at their own speed in their own way, to model themselves after people they admire and to face challenges that inspire them. Every day. That’s how humanity advances.

The future is too important to do otherwise.

, when children spend time in natural areas their play is more creative and they self-manage risk more appropriately. They’re more likely to incorporate each other’s ideas into expressive make-believe scenarios using their dynamic surroundings—tall grasses become a savannah, tree roots become elf houses, boulders become a fort. Their games are more likely to incorporate peers of differing ages and abilities. Regular outdoor experiences not only boost emotional health, memory, and problem solving, they also help children learn how to get along with each other in ever-changing circumstances. Free outdoor play with others, especially when it’s not hampered by adult interference, teaches kids to interact with others while also maintaining self-control. Otherwise, no one wants to play with them. It’s the best sort of learning because it’s fun. Sounds like the perfect way to raise bully-proof kids doesn’t it?