Amy Heath is a writer, poet, and artist. The past few years she’s lived a somewhat nomadic life, exploring ways to sustain herself while being true to her spirit.

I met Amy when she was a children’s librarian and children’s book author, back when I spent a lot of time in the picture book section with my four kids. I was drawn to her friendly blue eyes and gentle manner. I cherished our brief, always lively conversations. I’d walk away thinking how much I’d like us to be friends but I was too shy to ask if we could get together because she was vastly cooler and far more fascinating than I’d ever be. Fast forward to the last few years, when Amy befriended me. I’m giddy about it in a can’t-believe-my-luck sort of way.

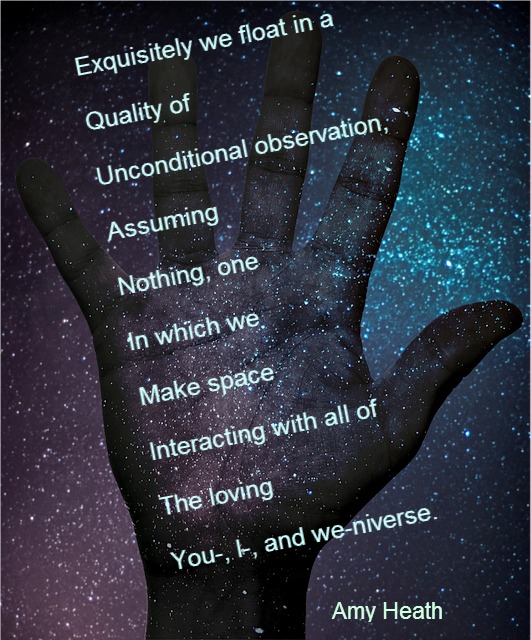

One of the many things Amy is up to lately is a poetic challenge. About a year ago she decided she’d write an acrostic poem a day. Being Amy, she amped up the challenge by making a rule for herself that the acrostics must be composed around words chosen at random from a book or words others chose for her.

a·cros·tic (ə-krô′stĭk, ə-krŏs′tĭk) n.

1. A poem or series of lines in which certain letters, usually the first in each line, form a name, motto, or message when read in sequence.

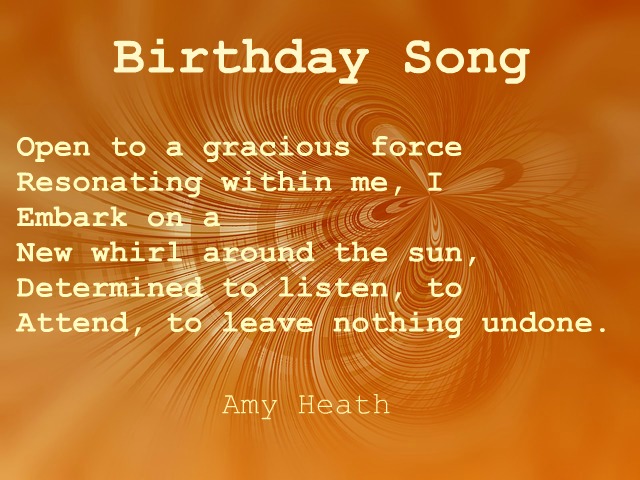

“The main point of this project was to play with words every day until I reach 60,” she says. “Until that idea struck me, I had been writing acrostics in a more serious vein, on words like mindfulness, anxiety, patience, empathy. I have seen many people approach the Big 6-0 with trepidation. Well, I would play my way there!”

And no matter what, she vowed to post each piece on her blog, Unraveling Y. She says, “After reading the book Show Your Work by Austin Kleon, I decided that if I blogged these short daily creations I would feel somehow more accountable to my intention. My wordplays would be out there. And being fairly sure that very few people would read them, I felt liberated to do my best without worrying about what anyone thought of them. That’s good practice anyway. Worrying about what other people think is trespassing in their heads. Not cool.”

Amy’s poems find an inner presence in words, making each one into something so alive we can feel it breathe, as she does with equanimity.

Even in the space of a few syllables.

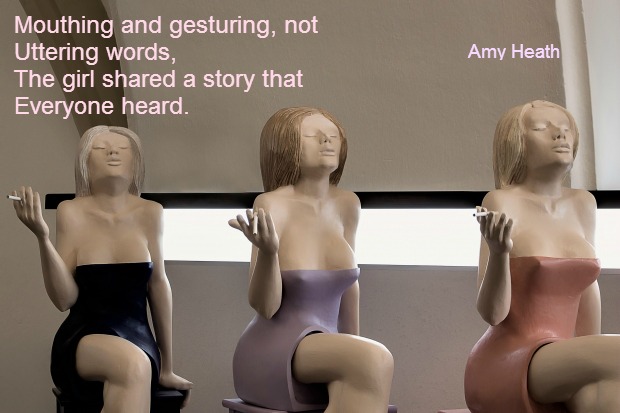

She turns a word into a tale that leaves us wondering.

She helps us understand why the Latin word for hearth has come to mean “center of activity.”

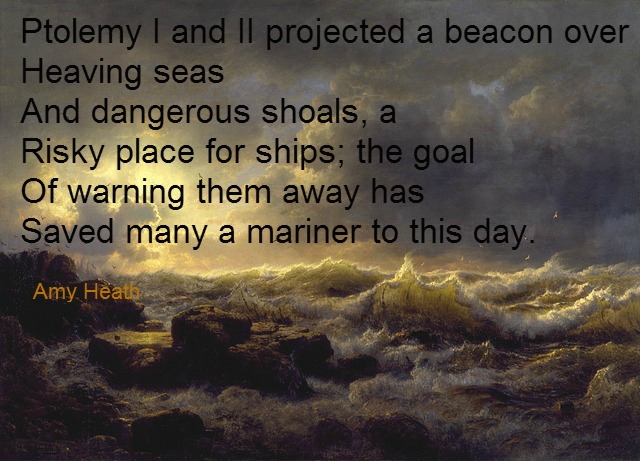

She shares little known history, explaining in her blog entry: “The lighthouse built by Ptolemy I Soter and completed by his son Ptolemy II Philadelphus was a prototype for subsequent structures. Pharos, a small island, ultimately the tip of a peninsula near Alexandria, became the root word in many languages for lighthouse.”

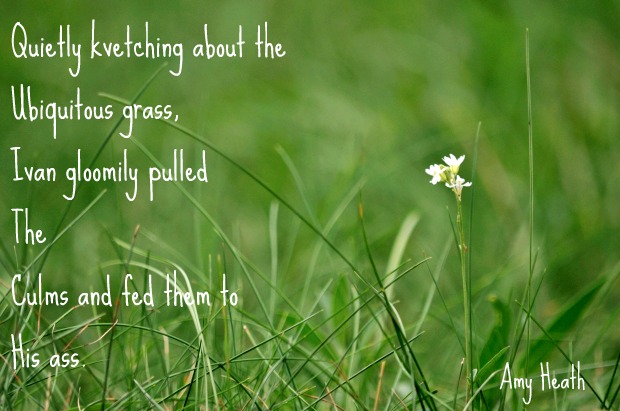

She’s undaunted when faced with a word like quitch.

Among my favorites is a poem she composed around the word orenda, which is defined as “a supernatural force believed by the Iroquois to be present, in varying degrees, in all things and all beings, and to be the spiritual force underlying human accomplishment.”

Amy is brimming with acrostic-related ideas. She may write a book on a single theme or compose a children’s story using words for various literary devices. She may illustrate her poems using paint or yarn or glass. The future is open for my playfully creative friend.

What is she seeking right now?

Words.

She’s continuing her daily acrostic challenge and invites you to send her a word which she’ll gladly transform into a poem. Her email is unravelingy@gmail.com

While you’re at it, I suggest you:

visit her blog Unraveling Y

read her memoir I Pity The Man Who Marries You

share her poems on social media

contact her to let her know how much you enjoy her work

consider embarking on a challenge of your own!