History is always relevant.

It’s the quiet reminder found in old buildings, tall trees and important decisions. It is present in the way we do things, although we rarely stop to realize that we do things a certain way because it was done that way in the past. When children ask “why” we often realize we don’t know. Figuring out the answer invariably leads us back to history.

Each of us is the product of history. Our lives today are evidence that our ancestors survived unbelievable odds stretching back to prehistory. The ground we stand on and the flesh we are composed of is not new, each atom has history.

Taking a fresh look at the past is a great way to provide meaning for our lives today. Here are some ways to make history come alive for you and your family.

Imagine history. Take a walk in a natural area while thinking about how earlier peoples used resources they encountered. What could be utilized to hold water, provide shelter and heat, to cut or pound foods, to heal, to defend? How would natural conditions affect the stories, celebrations and religion of the region? What evidence might be left behind by the earliest inhabitants?

Take a walk in the city and ask children to imagine it as it was long ago. Notice buildings that were standing more than 100 years ago, talk about what sounds may have been heard then, ask what sort of businesses and transportation they would have seen.

Investigate the past in your backyard. See what you find in the ground before putting in a new garden or extending the patio. Learn about the people who lived in the area long before you by researching the settlement of the town, early explorers, and original inhabitants. Discover what you can about the history of your home and previous owners. Check out Discovering the History of Your House: And Your Neighborhood by Betsy J. Green.

by Betsy J. Green.

Develop a book of family lore. Compile family recipes and any anecdotes that go with these foods. Add family sayings, funny stories, traditions, timelines, anything you’d like to record for coming generations.

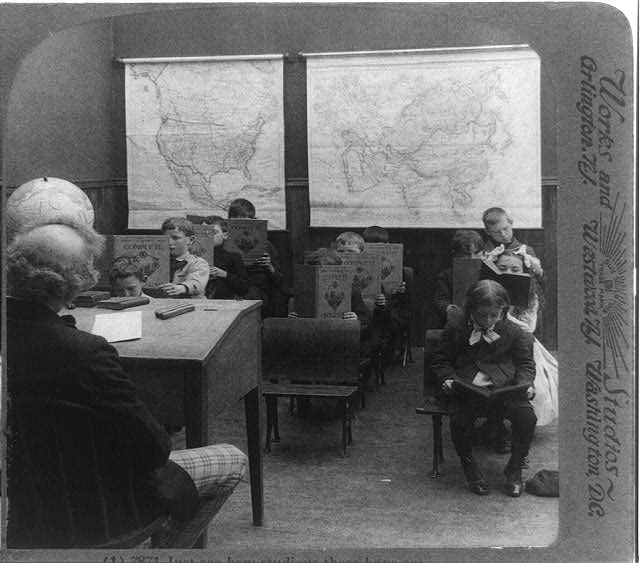

Enjoy history brought to life. Check out Living History offerings to witness life as it was in the past. Enter terms such as “open air museum,” “folk museum,” “living history” and “living farm museum” into a search engine to find listings for your area. Such places provide immersion experiences, hands-on workshops, and history theater.

Don’t forget historical reenactments. Reenactment organizations use meticulous care to replay pivotal events. And there are the ever popular Renaissance fairs filled with entertainment, jousting tournaments, art and foods.

Emphasize the importance of primary documents. Rather than relying on the interpretations of others, discover what history has to say through letters, photos, deeds and more. Consider Eyewitness to History and American Memory Project. For information on using primary documents go to The National Archives.

Use the past today. When facing an ordinary quandary, think back to how the same sort of problem was handled in the past. This is particularly effective on a personal level. History helps us learn from the actions of others. We can see the long term effects of mistakes and faulty reasoning. We can also see the results of highly ethical choices. A consideration of history helps develop good judgment.

Explore your heritage. It’s likely your family tree branches out into several regions or countries. Find out about the stories, customs, foods, inventions, struggles, and successes that make up your cultural background.

Dig into archeology. This field connects history, anthropology, art, geography and more. History is underground awaiting discovery, just as our era will someday be a mystery to future archeologists. Children may be inspired to set up a backyard dig. They may want to wire bleached chicken bones back into a skeleton or excavate a garbage can for lifestyle “clues.”

Dig offers links, art and a state guide to educational events. For younger children, try Archaeologists Dig for Clues by Kate Duke. For preteens, look into Archaeology for Kids: Uncovering the Mysteries of Our Past

by Kate Duke. For preteens, look into Archaeology for Kids: Uncovering the Mysteries of Our Past by Richard Panchyk.

by Richard Panchyk.

Maintain a special trunk, box or storage container as a personal history cache for each child. Keep copies of photos, artwork, letters, special ticket stubs and programs, mementos such as a forgotten toddler toy, notes about the child’s humorous sayings, a lock of hair, even a few baby teeth saved from the Tooth Fairy.

See history as a mystery. The clues in letters, photographs and everyday items tell the story of people who can no longer speak for themselves. Books that children will enjoy are The Mary Celeste: An Unsolved Mystery from History and Roanoke: Roanoke: The Lost Colony–An Unsolved Mystery from History

and Roanoke: Roanoke: The Lost Colony–An Unsolved Mystery from History both by authors Jane Yolen and Heidi Elisabet Y Stemple. For older youth, enjoy Unsolved Mysteries of American History

both by authors Jane Yolen and Heidi Elisabet Y Stemple. For older youth, enjoy Unsolved Mysteries of American History

by Robert Stewart.

Indulge in biographies and autobiographies. This is a great way to learn how the conditions of the time impacted individual lives. It also gives insight into character formation. It’s helpful to let your child choose who he or she would like to read about. Even if your child tends to prefer specific biographies, say only sports bios, he’ll be learning how different eras shape a person’s life.

Gain perspective by playing historical games. Playing long-forgotten games helps us recognize that people in earlier eras were also youngsters who longed to have fun. For example, nineteenth century immigrant children in crowded U.S. cities played games that fit on stoops, sidewalks or a section of the street. Classic pastimes like stickball, scully (bottle caps), marbles, and hopscotch were inexpensive amusements for children even in the poorest families. Enjoy games from other cultures. Check out or the book Kids Around the World Play!: The Best Fun and Games from Many Lands by Arlette N. Braman

by Arlette N. Braman

Value stories from your own family history. Tell your children stories of your childhood and what current events were going on at the time. Solicit stories from older members of the family. Encourage your children to ask their elders questions such as, “What made your family come to this country?” and “What was your first job?” and “What was it like when you were my age?” Display photos of ancestors and mention what you knew of their history. This provides children with a sense of continuity. It also helps them recognize that those who came before them contributed to who they are now.

Record oral history. Family members are a good way to start, but consider those in the community as well. Everyone has stories to tell, it’s a matter of finding out what topics are the catalyst. Be prepared with questions but remember to avoid interrupting. Start out with comfortable topics and work toward any that may be more intense. Let the interviewee talk and the conversation go in unexpected directions.

You may want to collect oral histories of a specific era, relevant to your ancestry or on a topic of interest. Augment this oral history with photographs, music and artwork.

Springboard into history using interests. If your daughter is an adventurer at heart, she can learn how explorers, inventors, navigators, and wanderers changed the course of history with the same intrepid desire to “find out” that she has. If your son likes cartoons, he can discover similar drawings made for political commentary, social satire, and storytelling that show such artists as unafraid to advance ideas through deceptively simple sketches. Those earlier cartoonists made the medium what it is today.

There’s a historical angle to any interest. Whether your child has a passion for airplanes, stand-up comedy, glassblowing, or skiing there’s a back story to be discovered that makes history relevant to who your child is right now.

Act it out. Learning about Napoléon? As a child the future emperor was bullied by older students, that is until he led younger boys to rout their elders in a successful snowball battle (hinting at his nascent leadership skills). It might look something like this. Dramatic moments in history are perfect to reenact in the back yard or park.

Learn about time capsules. Documents and artifacts are vital historical evidence. Sometimes such evidence is discovered hidden away in an attic, trunk or archeological dig, creating a kind of unintentional time capsule. Many people leave time capsules, either to be opened themselves a few decades later or to leave for future generations. Make a time capsule together, filling it with personally and historically relevant items.

Learn about Golden Record included in both Voyager spacecraft launched in the late 1970s. Find out what it included and why. This message was sent along: “This is a present from a small, distant world, a token of our sounds, our science, our images, our music, our thoughts and our feelings. We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours.”

Put yourself in history with fiction. Good books help young people imagine themselves in another place or era. Try an activity mentioned in the book such as darning a sock, shooting a slingshot, or foretelling the future through dreams. A Book in Time offers a chronological list of children’s books, plus crafts and other project ideas.

Time travel. Ask yourself “what if” questions to stimulate thinking about different outcomes. “What if the Black Plague never occurred?” or “What if the Allies had lost World War I?” Ask what event or decision in history you would most like to see altered, and why. Ask what person from the past you would most like to meet, and what you would ask him or her.

Let periodicals bring history to your door. A freshly delivered magazine is enticing. There are wonderful historical and cultural magazines for children including Calliope: World History for Kids, Cobblestone: American History for Kids and Faces: People, Places and Cultures.

Make a gift of family history. Give the tiny leather case with great grandma’s reading glasses to your daughter, along with your memory of this lady who loved to write. This might mean a great deal to a teenager who harbors ambitions of becoming a novelist. The pocketknife from a great uncle who left to seek his fortune as a merchant marine, and who sent letters from ports all over the world may be a meaningful gift for your son who talks of setting off on his own travels.

Cook historically. Try some of the characteristic foods and preparation techniques from the past. Cook stew over a fire, taste plantain, make hasty pudding, grind buckwheat. Ever wonder when people began eating certain foods or developing distinct recipes? The Food Timeline offers a look back, with each foodstuff clickable to an historical article.

Hold a fair. Some homeschool and enrichment groups have a yearly fair oriented toward history or social studies. Consider a biography fair, genealogy fair, history fair, or international fair. For example, at an international fair each young person sets up a display for the country or region they’ve chosen. They might have posters, projects, foods to sample, crafts and interactive activities. Each participant comes prepared to lead a game from the country they studied, making the fair a lively event. Some groups might also require each participant to provide a hand-out so that everyone leaves with information about all countries featured at the fair.

Visit graveyards. Cemeteries have stories to tell. Children can learn about family size, immigration and wartime. They can look for the most unusual names, notice the frequency of childhood death in different eras, write down interesting epitaphs. Discuss in advance the necessity for showing respect for gravesites and acting with decorum.

Oakland Chinatown StreetFest

Explore the impact of culture. Immerse yourself in a culture’s art, music and stories. Learn about legends and beliefs. How do these aspects affect the way those people organized their societies and lived their lives? Who would you be in that society? How would your worldview change if that were your culture? Notice similarities and differences in current times.

Look at your life as an historian or anthropologist might. What’s called “folklife” is simply the everyday creativity surrounding us right now. Jump rope chants, ghost stories, jokes, the way your parents or grandparents warn you to behave, celebrations and daily rituals—these are folklife. The memories you are building right now are history in the making.

These ideas are excerpted from Free Range Learning: How Homeschooling Changes Everything.

Additional Resources

Online

Odyssey provides interactive learning about the Near East, Egypt, Greece, Rome, Africa, and ancient Americas.

BBC History offers a wealth of information from ancient to recent history through in-depth articles, animations, games and videos.

History Matters emphasizes the use of primary sources in text, image and audio.

HyperHistory Online presents world history through interactive timelines, maps, images and text files.

World Digital Library offers multilingual primary materials to promote current and historical understanding.

Books

Around The World Crafts: Great Activities For Kids Who Like History, Math, Art, Science And More! by Kathy Ceceri

by Kathy Ceceri

A Street Through Time by Anne Millard

by Anne Millard

A City Through Time by Philip Steele

by Philip Steele

Constitution Translated for Kids  by Cathy Travis

by Cathy Travis

Turn of the Century by Ellen Jackson

by Ellen Jackson

We Were There, Too!: Young People in U.S. History by Phillip Hoose

by Phillip Hoose

wrote in a recent New York Times op-ed that declining verbal scores have to do with enduring school days stripped of “substantial and coherent lessons concerning the human and natural worlds…” He goes on to note,

: