My teenaged son just spent the day with middle-aged guys he met online.

Let me explain. Before he could drive, my son earned enough money shoveling out horse stalls to buy a 1973 Opel GT. Or what was left of one.

The car sits out back in a dark barn, its classic little outline like a rough sketch waiting for functional automotive details to be filled in again. He is restoring it himself, but not alone. He’s in touch with an online community of automotive enthusiasts from around the world. They eagerly share experiences and resources on forums. They also boast, complain, and talk about their interests just as any friends do.

My son and his father have met some of these folks at auto meets and car shows. When my son discovered an Opel club not far from our family farm he was invited to join. Today he and his older brother drove out for a day-long gathering. Although my boys were the youngest by decades they enjoyed an open-hearted welcome.

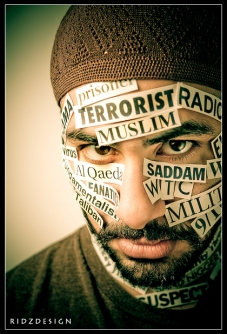

Yes, I realize there are significant concerns about teens talking online with adults, let alone meeting them. I try to keep those concerns in perspective. Studies of online behavior by youth indicate the biggest risk they face is peer harassment, not sexual predation. Today’s young people are much more overprotected than previous generations even though violence against kids has markedly decreased and the overall crime rate continues to plummet. Overly cautious, restrictive parenting practices actually inhibit a teen’s growth toward maturity and responsibility. So I watch, ask questions, and recognize that my son benefits from online friends and mentors.

It’s a pivotal coming of age experience to be accepted by elders one admires. Until that time it’s hard to feel like an adult. These experiences are frequently depicted in movies, but children and teens in our culture are almost entirely segregated from meaningful and regular involvement with adults.

These days kids spend their formative years with age mates in day care, school, sports, and other activities. So their adult role models are largely those whose main function is to manage children. This subverts the way youth have learned and matured throughout human history. Children are drawn to watch, imitate, and gain useful skills. They want to see how people they admire handle a crisis, build a business, compose music, repair a car, and fall in love. Separate kids from purposeful, interesting interaction with adults and they have little to guide them other than their peers and the entertainment industry. That’s because our species learns by example. Ask any child development expert, neuroscientist, or great grandparent.

There are plenty of educational initiatives to bridge this gap, particularly for teens. These programs connect students with mentors or bring community members into schools to talk about their careers. While these efforts are admirable, such stopgap measures aren’t the way young people learn best. They need to spend appreciable time with people of all ages—observing, conversing, and taking on responsibility. Real responsibilities, real relationships.

Because my kids are homeschooled they’ve have more opportunities (and a lot more time) to hang out with interesting adults. My daughter volunteers for hours each week alongside a woman who rehabilitates birds of prey. Another of my sons has played bagpipes for years with an 80-something gent who once served as a Pipe Major for Scotland’s Black Watch. The age range of my kids’ friends spans decades. Natural mentors such as these are a rich source of authentic experience. And they’re in every community. It’s not hard to find them.

Along with other homeschooling families, my kids have also taken a close look at the workaday adult world. The owner of a steel drum company explained the history and science of drum-making, talked about the rewards and risks of entrepreneurship, then encouraged us to play the drums displayed there. An engineer took us through his testing facility and showed us how materials are developed for the space program. We’ve spent days with potters, woodworkers, architects, chemists, archeologists, stagehands, chefs, paramedics and others.

People rarely turn us down when we request the chance to learn from them. Perhaps the desire to pass along wisdom and experience to the next generation is encoded in our genes. Age segregation goes both ways–adults are also separated from most youth in our society. After an afternoon together we’ve gotten the same feedback again and again. These adults say they had no idea the work they do would be so interesting to kids. They marvel at the questions asked, observations made, and ideas proffered by youth that the media portrays as disaffected or worse. They shake hands with young people who a few hours ago were strangers and say, “Come back in a few years, I’d like to have you intern here,” or “We could use an engineer who thinks the way you do. Think about going into the field,” or “Thanks for coming. I’ve never had this much fun at work.”

So today my teenaged son hung out with fellow Opel aficionados. They trust he will drive his car out of the dark barn and into the sunlight soon. It will be a shared accomplishment, the kind of thing that happens all the time when young people aren’t separated from the wider community.

I wrote this piece nearly two years ago for Shareable.com. Since then this son of mine has become a mechanical engineering student at a private college. His fellow classmates brought with them years of advanced placement math and science classes. The advantage he brought? Lots of hands-on experience, an active approach to learning, and insatiable curiosity. He’s at the top of his class.