“It is becoming increasingly clear through research on the brain, as well as in other areas of study, that childhood needs play. Play acts as a forward feed mechanism into courageous, creative, rigorous thinking in adulthood.” ~ Tina Bruce

Nine-year-old Charlotte has one hand slung around a utility pole as she slowly twirls, her head tipped to watch the upper floors of her Cleveland apartment building circle past. Her mother is unloading groceries and chides her daughter, “Stop playing around!”

Charlotte actually has very little time to play. Her days are tightly woven as the dozens of perfectly tended braids in her hair. She’s in the gifted stream at school, participates in swim team and basketball team, takes clarinet lessons, and attends a computer-oriented STEM program on Saturdays.

“I had more of a Little Rascals childhood,” Charlotte’s mother says. “My girlfriends and I would use sheets hanging on the clothesline as curtains to perform Michael Jackson hits or I’d ride bikes with my brothers down dirt piles pretending to be Evel Knievel. It was a lot of fun but Char has more advantages than I could have dreamed of.”

Charlotte’s mom needs to get the groceries unpacked before heading back out. She’ll drop Charlotte off at basketball practice, then buy craft supplies her daughter needs to make a school project. “It’s endless,” she says. “We’re running all the time.”

Although she’s in a hurry, she has more to say about play. “The other day Char had friends over,” she says. “They were whispering and giggling. I felt bad that I had to barge in and tell the girls their playdate was over because we had to leave. I know they need more time to just be silly.”

She’s right.

Most adults don’t hesitate to interrupt play with an activity they assume is more important or to halt play they deem too loud, messy, or rough. And they don’t see a problem with corralling children’s leisure time in ways that remove most aspects of “free” from play. Dismissing what kids do as “just” play also denies what makes us fully ourselves.

There’s no definitive description of free play, but as author and play advocate Bob Hughes wrote back in 1982, it’s behavior that is “freely chosen, personally directed, and intrinsically motivated, i.e. performed for no external goal or reward.”

Psychiatrist Stuart Brown, founder of the National Institute for Play, expands on this. He says play basics include purposeless, repetitive, pleasurable, spontaneous actions. Play takes many forms. Sometimes this is driven by curiosity and the urge to discover. Sometimes it’s imaginative play driven by an internal narrative. Sometimes it’s rough and tumble play, the kind that necessarily puts the player at risk and involves anti-gravity moves such as jumping, diving, and spinning.

Picture the wildly free play of puppies and kittens as they wrestle and explore; that’s what he is describing. As Dr. Brown writes, “The urge to play is embedded within all humans, and has been generated and refined by nature for over one hundred million years.”

Ever taller stacks of research demonstrate that free play is critical for development. It fosters problem-solving, reduces stress, enhances learning, and boosts happiness.

Make-believe games go a long way toward helping kids develop self-regulation, including reduced aggression, ability to delay gratification, and advancing empathy. One form of make-believe, more common in children who have lots of minimally unsupervised free time, is called worldplay. This is considered the apex of childhood imagination and is linked with lifelong creativity,

Preliminary studies indicate the less structured time in a child’s day, the better their ability to set goals and reach those goals without pressure from adults. Childhood play is even correlated with high levels of social success in adulthood.

And, as if we didn’t already know this, free play generates sheer joy. The BBC series “Child of Our Time” studied play. They found the more children engaged in free play, the more they laughed, particularly when playing outside. The kids who played the most laughed up to 20 times more than kids who played less. This is surely the best reason of all to play.

But then it strikes us. Suddenly, with the same horrified expression mad scientists wear in sci fi movies while uttering the lines, “What have we done?” we realize that we’ve squeezed nearly all the free play out of childhood. If there are monsters in this scenario, they come disguised as tighter safety restrictions, more adult-run activities, insufficient recess at school, and the lure of screens. Since the 1970’s children have 25 percent less time to play, with 50 percent less time in unstructured outdoor play. In the 1980’s, school-aged children spent 40 percent of the day, on average, engaging in free play. By 1997, that average had dwindled to a mere 25 percent and continue to decline. A recent report notes that American kids, on average, spend about four to seven minutes a day playing outside but over seven hours a day in front of screens. Even when kids do have time to play freely, it’s now common for adults to supervise.

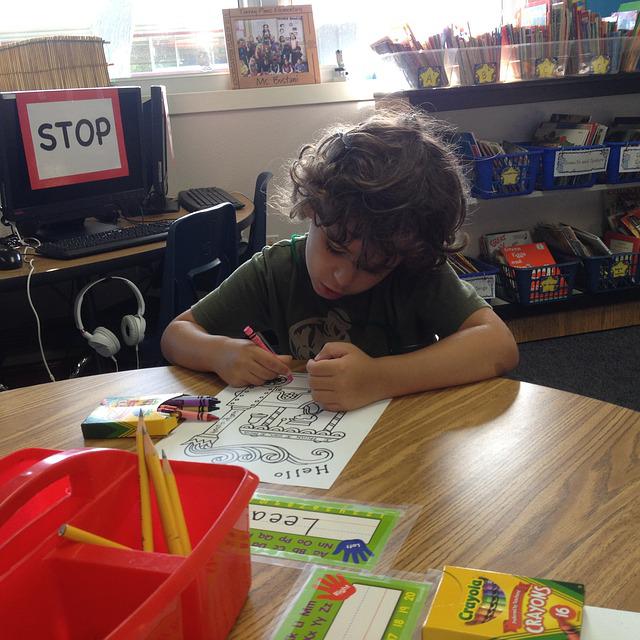

This is particularly true in educational settings. Play is a buzzword for educators, but as Elizabeth Braue wrote in a journal article titled “Are We Paving Paradise?” — “What counts as play in many classrooms are highly controlled situations that focus on particular content labeled as ‘choice’ but that are really directed at capturing a specific content-based learning experience, such as number bingo or retelling a story exactly as the teacher told it on a flannel board.” Free play, particularly the more emotionally expressive and physically active forms, are also squeezed out of daycare and afterschool programs in favor of planned activities.

It’s not just a U.S. thing. A structured and heavily supervised childhood is becoming more prevalent globally. When thousands of mothers around the world were asked about their children’s activities, they tended to agree that a lack of free play and experiential learning was eroding childhood. At the same time, they listed their children’s main free-time activity as watching television. This held true for children growing up in North and South American, Europe, Asia, and Africa. The researchers, writing in the American Journal of Play, made clear their surprise at what they called a “homogenization of children’s activities and parents’ attitudes.”

Marketing messages are so ever-present that they’ve reshaped the norms for raising children. Those messages lead us to believe that good parents heavily supervise children, keeping them busy with purchased playthings and pricey programs starting in toddlerhood or earlier. Such opportunities, we’re told, are found in specialized toys, educational apps, adult-run programs and lessons, gym and fitness sessions, organized sports, and extra-curricular activities. This presumes the kind of spending power and free time that’s entirely out of reach for most US parents. The cost is greater than money because they also lose family time, relaxation, and free play.

That’s not to say a child shouldn’t take drum lessons, go to the rock climbing gym, or participate in scouts. The difference between an overscheduled child and a child who’s eager to take on more activities has to do with each child’s unpressured choices, balanced with what’s best for the family as a whole. It’s also worth remembering that shuttling our kids around for enrichment activities is not necessarily correlated with later success.

Play is a constant in the life of young children. When we formalize it with too many activities that turn play into a tool for academic or physical advancement, we lose sight of play for play’s sake.

This is an important consideration, because the short and long-term consequences of too little free play are more serious than most of us imagine. Play deprivation (yes, it’s a term) has been linked to significant problems. At the most extreme is the potential for increased criminal behavior. Dr. Brown has studied the topic for 47 years, conducting something like six thousand individually conducted play histories. He was initially drawn to learn more when he looked for common backgrounds among men convicted of felony drunk driving and men convicted of homicide. To his surprise, he found these individuals shared a background of severe, sustained, long-term play deprivation. More recent studies have identified play deprivation as a factor in violent crimes committed by juveniles.

Overscheduled kids aren’t more likely to commit crimes, by any means. Much more research needs to be done to establish a causal link. But we do know that too little free play is serious problem. Youth mental health continues to worsen—with particularly stark increases in problems among teen girls. Nearly 1 in 3 girls seriously considered attempting suicide—up nearly 60% from a decade ago. Across all racial and ethnic groups teens are experiencing increasing rates of persistent sadness or hopelessness.

- Over 20 years ago, David Elkind wrote in The Hurried Child: Growing Up Too Fast Too Soon, that overscheduled children and teens are more likely to show signs of stress, anxiety, and depression. It’s thought that free play and quality family time are a protective effect, helping children work through and manage such feelings.

- Peter Gray finds it logical that a decline in play might result in increased emotional and social disorders. He writes in Free To Learn, “Play is nature’s way of teaching children how to solve their own problems, control their impulses, modulate their emotions, see from others’ perspectives, negotiate differences, and get along with others as equals. There is no substitute for play as a means of learning these skills.”

- Physical play is critical in maintaining good mental health and a useful intervention when young people suffer from depression. A recent study found physical activity at least three times a week resulted in a significant reduction in depression symptoms. The effect was greatest “when the physical activity was unsupervised than when it was fully or partially supervised.”

Play is humanity’s spark plug. It connects us to a current that exists within us and around us, an aliveness that runs on fun. This is how we make scientific advances; how we develop products that were once in the realm of fantasy; how we create music, books, movies, games, and art; how we laugh with friends, build community, and come up with solutions. It’s no wonder all of us need more play.

When Charlotte notices her mother is caught up in conversation with me, she runs up the staircase outside their apartment and slides her backpack down the railing, then tries to scurry down the steps fast enough to catch it. When she succeeds on the second try, she boosts the challenge by running down the mulched dirt on the outside of the steps. An elderly man approaches the steps. She pauses, perhaps wary of his disapproval. Instead he playfully slides the backpack back up just as she nears the bottom. Charlotte’s mother turns around when she hears her daughter’s giggle join the older man’s hearty laugh. It’s a lighthearted moment of connection for all four of us, brought into being through playfulness. “That’s the great thing about kids,” she says. “They can turn anything into play.”

So can we all. I don’t think anyone says it better than games expert and play advocate Bernie DeKoven, who wrote in A Playful Path,

“Playfulness is a gift that grants you great power. It allows you to transform the very things that you take seriously into opportunities to shared laughter; the very things that make your heart heavy into things that make you rejoice, it turns junk into toys, toys into art, art into celebration. It turns walking into skipping, skipping into dance. It turns problems into puzzles, puzzles into invitations to wonder.”