Fascinations have a way of capturing me and there’s no telling where they might take me. One topic that recently got its teeth into me is, well, eels. It all started with a story.

In a Swedish village called Brantevik, an eight-year-old boy named Samuel tossed an eel into his grandparent’s well. This was in 1859, the same year that John Brown raided the Harpers Ferry Armory. The year Charles Darwin published On The Origin of Species. The year the horrific Battle of Solferino, in Italy, inspired the founding of the Red Cross. A long time ago.

Eels were commonly put into wells to control vermin, so Samuel’s grandparents left the creature there. Little Samuel named the well-dwelling eel Åle, which is an appropriate name seeing as it’s the word for eel in Swedish. Åle turned out to be quite the eel…

I ran across this story in the marvelous book, Eloquence of the Sardine: Extraordinary Encounters Beneath the Sea (indie link) by Bill Francois. The author explains that all eels in Europe were born in the depths of the Caribbean, most likely the evocatively named Sargasso Sea. Newborn eel larvae are transparent and about a sixteenth of an inch long. (Image below from the Twitter feed of @DrEmilyFinch.)

Somehow these small toothed creatures swim thousands of miles, months on end, without stopping. Along the way they take on the characteristic serpentine shape. When they reach a river’s mouth they swim upstream. At this stage they are no longer considered glass eels, they are elvers, and transform from saltwater creatures to freshwater creatures.

This is already a lot to go through, but an eel’s determination is incredible. When it picks a river to traverse in search of a quiet stretch to live, it is undaunted. If the expected swamps and waterways have been replaced by farms or pavement, the eel will crawl over land for days. Or it will wiggle through a pipe, even subterranean water table, until it reaches a stream. When it has finally chosen a freshwater home it will remain there, some for a decade or so.

Eventually something beckons the eel back to the sea. Although it has been yellow-skinned while living in fresh water, once it’s ready to go back to the sea it transforms again. Its skin thickens, stomach shrivels, eyes enlarge, head streamlines, and its color changes to silver. It embarks on a many-month journey back to the place of its birth. According to The Book of Eels: Our Enduring Fascination with the Most Mysterious Creature in the Natural World (indie link) by Patrik Svensson, it navigates using olfactory sensitivity, perhaps also by sensing the Earth’s magnetic lines, and keeps to extreme ocean depths for safety. The journey back is brutal. Eels are weakened by pollution, eaten by many predators, prone to infection and infestation, and even at journey’s end can be blocked by damns and other constructions. If it arrives, here it will mate. Or presumably mate, as no one has seen mature eels in the Sargasso Sea. These final mysteries conclude the eel’s lifespan.

But if an eel, determined to make the final trip back to its birthplace, cannot make it to the sea it will switch back from silver to yellow and wait. And wait. This may serve many of them well. Branches blocking a waterway or pipes blocked by debris may eventually clear. Eels trapped in freshwater have epic patience.

Åle, the eel left in the well, had no way to make this return journey. It simply waited for its pathway to the sea to reopen. It waited as Samuel grew up, then waited as generations of Samuel’s family were born, lived, and died. Occasionally the local papers wrote about Åle. Eventually another eel was tossed in the well as a companion. The long-lived Åle gained notoriety in Sweden. It was featured on television and in children’s books. It lived longer than Pute, an eel kept in a Swedish aquarium for 85 years. It lived longer than any eel on record.

Duing that time, adult eels suffered from overfishing and eel larvae became a delicacy in some Asian countries. Waterway pollution and habitat destruction added even more pressure on the species. The population of these hardy creatures declined by 90 percent and they were put on the critically endangered list. Åle remained in the well, still waiting to swim back to the Sargasso Sea. That little creature waited as humanity went on into the space age and into a time of worsening climate change.

Åle might be living still, who knows, if not for an unfortunate incident when the well water got so hot that the elderly eel died at the purported age of 155. His eel companion, age 110, is said to still wait for its route the sea to open.

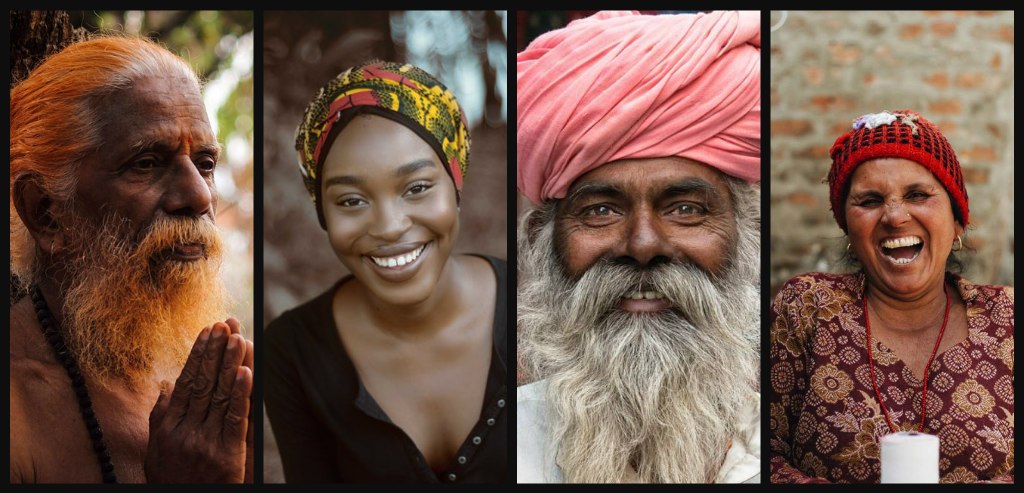

I don’t know why I’m captivated by eels. Åle’s life, and much about these enigmatic and misunderstood creatures, seems like a mythic tale where one’s destiny is so vital that nothing can get in the way—not despair, not loneliness, not even mortality. It reminds me of those who wait a substantial part of their lives to let themselves be who they want to be. Or even to discover who they are becoming.

It reminds me, too, that transforming from youth to old age is anathema in our youth-obsessed culture. No one is clustering around elders for their stories and their wisdom as people did throughout nearly every era of human existence. It brings to mind the epic work being done by my friend, John C. Robinson, whose recent books include Mystical Activism: Transforming A World In Crisis (indie link) and Divine Human: The Final Transformation of Sacred Aging (indie link). John is engaged in what he calls his final works, writing mystical poetry shared weekly online and due out soon in book form. Surely our elders can help us begin to recognize what well traps us and how to transform ourselves for the journey home.