image: stratusphunk

My mother kept family stories alive by folding them into our lives as we grew up. She’d remark, “This would have been your Uncle John’s birthday,” and then she’d tell us something about him. Like the time he taught her how bad cigarettes were. That day he took her behind the garage and let her smoke until she was sick. (She was four years old.) Or how he skipped out on his college scholarship and pretended he didn’t have a bad back so he could sign up for the Air Force. His plane was shot down on his 47th mission, his body never found.

She told us about a great-great-grandfather, left to take a nap under a shade tree as a baby. He was taken by passing Native Americans, who may very likely have thought the tiny boy was abandoned. His parents didn’t go after him with guns, they brought pies and cakes to those who’d taken him to ask for him back.

She told us about a tiny great grandmother who expected other people to meet her every need, but when a candle caught the Christmas tree on fire that same helpless little grandmother immediately picked it up and threw it out the plate glass window to keep the house from burning down.

She told us about her Swedish grandmother who was widowed not long after coming to this country, but kept the family together by taking in laundry. And about the only son growing up in that family who ran away as a teen. They didn’t hear from him till he’d made a new life under a new name, years later.

My mother didn’t just talk about long-gone family members. She told us about people in our everyday lives too. She talked about dating our father, saying he was still the most wonderful man she ever met. She told us about meeting his sister and her husband for the first time—they were on the roof of the house they were building together, hammering down shingles. And she shared inspiring stories from friends, neighbors, and people she’d only read about. She never said it aloud, but her stories gave me the sense that I too had within me the sort of mettle and courage to handle whatever came my way.

Turns out there’s more value to stories than my mother might have imagined.

1. Child development experts say young children who know family stories have fewer behavior problems, less anxiety, more family cohesiveness, and stronger internal locus of control. When mothers were taught to respond to their preschool-aged children with what researchers call elaborative reminiscence, their children were better able to understand other people’s people’s ideas and emotions—a vital skill at any age.

2. Family storytelling provides remarkable benefits as children get older. Preteens whose families regularly share thoughts and feelings about daily events as well as about recollections showed higher self-esteem. And for teens, intergenerational narratives help them to shape their own identity while feeling connected

3. Researchers asked children 20 questions on the Do You Know Scale, such as:

- Do you know where your grandparents grew up?

- Do you know some of the lessons that your parents learned from good or bad experiences?

- Do you know the story of your birth?

Results showed that the most self-confident children had a sturdy intergenerational self, a sense they belonged and understood what their family was about. This sense of belonging was called the “best single predictor of children’s emotional health and happiness.”

(Here are some ways to naturally incorporate family stories into your children’s lives.)

I’ll admit, the stories my mother told throughout my childhood didn’t skimp on tragedy but always highlighted positive character traits. It wasn’t until I was much older that more shadowed family tales slipped out—stories of mental health problems, alcoholism, and lifelong rifts. Those stories are just as important.

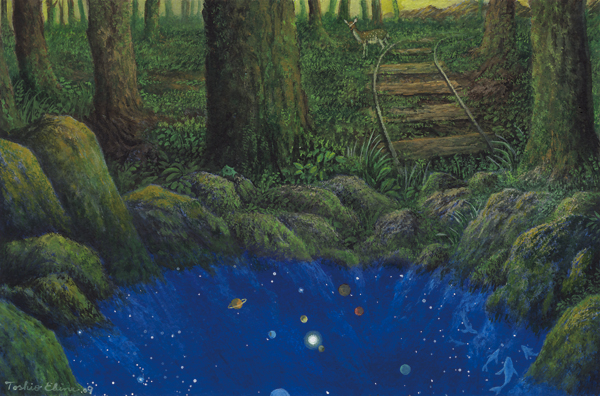

Our family tales are simply stories of humanity. All stories help to remind us what it means to be alive on this interconnected planet. Every day that passes gives us more stories to tell. Even better, more to listen to as well.

image: Navanna

. Oh, and be sure to bookmark his

. Oh, and be sure to bookmark his