It has been another long pandemic year with nearly every planned gathering, class, and adventure cancelled. Far far worse, this was also a year in which several friends died.

I am deeply grateful for wonderful people both irl and online, for the playful comfort of companion animals, for the mentors found in every one of nature’s inhabitants. And, as always, for the restorative pleasures of reading. Here’s a short look at some of the most memorable books I read this year.

FICTION

The Book of Form and Emptiness (indie link) by Ruth Ozeki

You know the feeling when you’re only a few pages in and recognize, through your whole body, you’ve stumbled on a magnificent book? One that is beautifully written by a person whose wisdom and insight will affirm what you haven’t ever been able to articulate? For me, The Book of Form and Emptiness is one such book. I adore the memory of Kenji, I understand Annabelle, I resonate with Benny, especially since we both recognize a soul in what others regard as “things.” I grieve the loss of Kenji, I am fascinated by The Aleph, I respect and admire Slavoj. And oh, the voice of Book, who speaks for all books, who knows and understands as I’ve always thought books did.

Here’s a glimpse of what Book has to tell us. ““Every person is trapped in their own particular bubble of delusion, and it’s every person’s task in life to break free. Books can help. We can make the past into the present, take you back in time and help you remember. We can show you things, shift your realities and widen your world, but the work of waking up is up to you.”

And another. “Is it odd to see a book within a book? It shouldn’t be. Books like each other. We understand each other. You could even say we are all related, enjoying a kinship that stretches like a rhizomatic network beneath human consciousness and knits the world of thought together. Think of us as a mycelium, a vast, subconscious fungal mat beneath a forest floor, and each book a fruiting body. Like mushrooms, we are a collectivity. Our pronouns are we, our, us.”

And, as a writer, I take this to heart. “The first words of a book are of utmost importance. The moment of encounter, when a reader turns to that first page and reads those opening words, it’s like locking eyes or touching someone’s hand for the first time, and we feel it, too. Books don’t have eyes or hands, it’s true, but when a book and a reader are meant for each other, both of them know it,”

Let yourself slide into this book while holding a book (or a tablet) believing it is also aware you are holding it…

Bewilderment (indie link) by Richard Powers

I was completely enraptured by this book. Powers deftly lets the reader inhabit what might be called a “different” mind via the excruciating awareness of a gifted child who is grieving the loss of his mother while simultaneously grieving his species’ relentless assault on Earth’s lifeforms. I felt for this child while also identifying with the father, who is experiencing these same trials while trying to lift his son toward a hopeful future. As the father notes, “Life is something we need to stop correcting. My boy was a pocket universe I could never hope to fathom. Every one of us is an experiment, and we don’t even know what the experiment is testing.”

There’s so much brought into this masterful book – science, faith, dedication, sorrow, beauty, creativity, judgement’s cruelties, and transcendence found in unspoiled nature. It also speaks to how those we love are never really gone. “Life itself is a spectrum disorder, where each of us vibrated at some unique frequency in the continuous rainbow.”

Okay, one more quote: “Oddly enough, there’s no name in the DSM for the compulsion to diagnose people.”

Lessons in Chemistry (indie link) by Bonnie Garmus

Triumph is not too strong a word for this debut novel. There’s so much intelligence and insight in this book — the main character, her young daughter, and the dog as notable examples. The author brings us directly into the unrelenting misogyny of the 1950s and 60s, doing so with respect for women who push back as well as empathy for women who do not. “Whenever you feel afraid, just remember,” Garmus writes. “Courage is the root of change – and change is what we’re chemically designed to do. So when you wake up tomorrow, make this pledge. No more holding yourself back. No more subscribing to others’ opinions of what you can and cannot achieve. And no more allowing anyone to pigeonhole you into useless categories of sex, race, economic status, and religion. Do not allow your talents to lie dormant, ladies. Design your own future. When you go home today, ask yourself what YOU will change. And then get started.”

This is a wise, savvy story with a generous backbone. It’s particularly jarring to see the cartoonish cover the publisher chose for this top of the class book — perhaps unintentionally reinforcing the theme that women have a great deal more to overcome.

Here’s one more exhortation the author offers. “No surprise. Idiots make it into every company. They tend to interview well.”

Nothing To See Here (indie link) by Kevin Wilson

Wildly improbable and incredibly engaging story about class division, hypocrisy, loneliness, responsibility, disability, and hope. You’ve definitely never read a novel about caring for fire-starting children while their politician father gets on with his career. Here are two quotes to enjoy:

“Who would judge you?” she asked. “Who do you know who’s done a good job? Name one parent that you think made it through without fucking their kid up in some specific way.”

“Timothy’s eyes kind of flashed with recognition, as if the seventeenth-century ghost who lived inside him had suddenly awakened.”

A Girl Called Rumi (indie link) by Ari Honarvar

Beauty, tragedy, and the lure of poetry carry us through back and forth between 1981 Shiraz, Iran and 2009 San Diego, as well as a realm beyond the physical world where mystical teachings of ancient Persia hold sway. “Tears pooled in my eyes as my mother’s recent poem came to mind, “ Honarvar writes. “It was about the four-thousand-year-old cypress that longed for the forest of her youth –before the insatiable darkness of winter devoured pleasant memories of blues skies and sunshine and before gardeners became lumberjacks.”

The Sentence (indie link) by Louise Erdrich

So much to savor from this prolific and deeply wise author. Here she writes about the power books (and tradition and love and fear) have over us. I love Louise Erdrich’s writing, including her wonderful Birchbark House children’s series. The Sentence absolutely flows, as if effortlessly served, and the characters stay with me. Here are a few quotes to give you a taste.

“You can’t get over things you do to other people as easily as you get over things they do to you.”

“Small bookstores have the romance of doomed intimate spaces about to be erased by unfettered capitalism.”

“Every world-destroying project disrupts something intimate, tangible, and Indigenous.”

Boy’s Life (indie link) by Robert McCammon

This is a rousing adventure story, a perfect distraction from current events. The main character, who entertains his friends with preposterous stories, is also living in such a story. While it’s mostly a coming-of-age tale told by an author who sometimes can’t help but bemoan the changes “progress” brings, it has just enough danger, mystery, and otherworldly strangeness to keep the reader going for 625 pages.

Here’s a quote I savored and shared years before actually reading this novel. “We all start out knowing magic. We are born with whirlwinds, forest fires, and comets inside us. We are born able to sing to birds and read the clouds and see our destiny in grains of sand. But then we get the magic educated right out of our souls. We get it churched out, spanked out, washed out, and combed out. We get put on the straight and narrow and told to be responsible. Told to act our age. Told to grow up, for God’s sake. And you know why we were told that? Because the people doing the telling were afraid of our wildness and youth, and because the magic we knew made them ashamed and sad of what they’d allowed to wither in themselves.”

It felt, reading this, as if McCammon was speaking directly to my experience. He writes, “It seemed to me at an early age that all human communication — whether it’s TV, movies, or books — begins with somebody wanting to tell a story. That need to tell, to plug into a universal socket, is probably one of our grandest desires. And the need to hear stories, to live lives other than our own for even the briefest moment, is the key to the magic that was born in our bones.”

And this. “When you look at something, don’t just look. See it. Really, really see it. See it so when you write it down, somebody else can see it, too.”

The Memoirs of Stockholm Sven (indie link) by Nathaniel Ian Miller

Stories have a strange magic. We come to care about the characters, especially when they evoke that stirring sense of “same” with the reader.

By the end of the book, I felt I understood Sven. What an interesting character. Here’s a man whose choices bring him little in the way of creature comforts, although he works tirelessly to keep himself alive, but who also thrives best when reading or observing nature. A man whose self-abnegation and disregard for others’ feelings shifts into a profound ability to connect and care thanks to those who have reached out to him. A man who judges entire nationalities as lazy, boorish, or stupid yet nearly every other character breaks free of prejudicial ideas about women’s roles, sex work, teen pregnancy, and war itself.

I enjoyed Sven’s curmudgeonly insights. Like this one. “A life is substantially more curious, and mundane, than the reports would have it. And in truth, though I am known—within the tiny dewdrop circles of the unlikely few who know of me—as a solitary, unmatched Arctic hunter, I am no such thing, and I was seldom alone.”

And my common ground with Sven’s love of reading. “I had no interest in destiny. I knew I wasn’t on the earth to please anyone, let alone God. I was just restless. National pride, military service, ribald songs, the sound of grown men laughing, air exchanged between several people in a tight space—they are all among the variety of things I found repellent. I suppose I still do. But they are also cherished staples of Swedish society. In the rather trite throes of alienation and disaffection, I turned instead, as so many youths before me have, to books.”

Much as I appreciated the character of Sven, I utterly adored Charles MacIntyre, Taino, and Skuld. If only a book’s magic would allow us to absorb and take on the qualities we most admire in its characters.

Eve Green (indie link) by Susan Fletcher

Fletcher is a rare writer. Her keen observations hold transcendent beauty, yet somehow she folds them into the story gently, without puffery. Her novel Corrag (released in the U.S. as The Highland Witch) is my favorite of hers but I’m holding back on reading all of her works, saving them the way one might save the good wine for a special occasion. Eve Green is her first novel, describing an orphaned girl growing up in her grandparent’s Welsh home surrounded by pastoral beauty as well as by painful lies.

“Love is blind, they say–but isn’t it more that love makes us see too much?” Fletcher writes. “Isn’t it more that love floods our brain with sights and sounds, so that everything looks bigger, brighter, more lovely than ever before?”

Unlikely Animals (indie link) by Annie Hartnett

A young woman returns home after dropping out of medical school, doing what she can to care for her father in this tragic yet witty story that somehow pulls together a missing person search, lost healing powers, a millionaire’s secret get-away, and a naturalist’s ghost in this story of intergenerational healing. Harnett writes, “Her father often said that a poet loves anything that better illuminates the daily horror of being alive.” This entertaining read seems too short, even at 368 pages.

Dancing in the Mosque: An Afghan Mother’s Letter to Her Son (indie link) by Homeira Quaderi

This is structured as a mother’s letter to the child she longs for. Her story asks us to consider the lives of Afghani women, their sacrifices, and what a mother will endure to protect the people she loves.

Quaderi writes, “My grandmother believed that one of the most difficult tasks that the Almighty can assign anyone is being a girl in Afghanistan. As a child, I didn’t want to be a girl. I didn’t want my dolls to be women.”

This Tender Land (indie link) by William Kent Krueger

This beautiful, disturbing, and absorbing novel has a lot in common with The Lincoln Highway — four kids on the lam with resulting violence as well as insight— except Krueger published this before Towles wrote his bestseller. I’m still troubled by the ending of Towles’ book. This Tender Land, in contrast, ends on a truly redemptive note. Here are two glimpses of Krueger’s writing.

“Our former selves are never dead. We speak to them, arguing against decisions we know will bring only unhappiness, offering consolation and hope, even though they cannot hear.”

“Me, I love this land, the work. Never was a churchgoer. God all penned up under a roof? I don’t think so. Ask me, God’s right here. In the dirt, the rain, the sky, the trees, the apples, the stars in the cottonwoods. In you and me, too. It’s all connected and it’s all God.”

NONFICTION

How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy (indie link) by Jenny Odell

The author reminds us our attention as the most precious—and overdrawn—resource we have. As she writes, “If we have only so much attention to give, and only so much time on this earth, we might want to think about reinfusing our attention and our communication with the intention that both deserve.” This book doesn’t rail at us to renounce technology and get back to nature (or our own navels). Instead it asks us to look at nuance, balance, repair, restoration, and true belonging. She writes beautifully. Here’s a snippet.

“In that sense, the creek is a reminder that we do not live in a simulation—a streamlined world of products, results, experiences, reviews—but rather on a giant rock whose other life-forms operate according to an ancient, oozing, almost chthonic logic. Snaking through the midst of the banal everyday is a deep weirdness, a world of flowerings, decompositions, and seepages, of a million crawling things, of spores and lacy fungal filaments, of minerals reacting and things being eaten away—all just on the other side of the chain-link fence.”

The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times (indie link) by Jane Goodall and Douglas Abrams

I really needed this book when I read, or actually listened to it. I don’t think the back and forth interview style enhanced the content but I loved hearing Jane’s voice on the audiobook. She shared stories about her wartime childhood, the disappointments that serendipitously led her to her life’s work, and about what it means to be an ambassador for a sustainable world. I was glad to hear her respond to vital questions such as “How do we stay hopeful when everything seems hopeless?” and “How do we cultivate hope in our children?” She says, “Hope is often misunderstood. People tend to think that it is simply passive wishful thinking: I hope something will happen but I’m not going to do anything about it. This is indeed the opposite of real hope, which requires action and engagement.”

Walking in Wonder: Eternal Wisdom for a Modern World (indie link) by John O’Donohue This is a posthumous collection from the Irish poet-theologian. I listened to the audiobook narrated by the author’s brother Pat O’Donohue. I play library CDs in my elderly car, so I absorbed this in small doses, which felt like a perfect way to appreciate O’Donohue all over again. And there’s so much wisdom here to absorb. For example, “If you go out for several hours into a place that is wild, your mind begins to slow down, down, down. What is happening is that the clay of your body is retrieving its own sense of sisterhood with the great clay of the landscape.”

Here’s another. “One of the sad things today is that so many people are frightened by the wonder of their own presence. They are dying to tie themselves into a system, a role, or to an image, or to a predetermined identity that other people have actually settled on for them. This identity may be totally at variance with the wild energies that are rising inside in their souls. Many of us get very afraid and we eventually compromise. We settle for something that is safe, rather than engaging the danger and the wildness that is in our own hearts. We should never forget that death is waiting for us.”

And one more, this from a man who died too young at the age of 52, “Walk around feeling like a leaf. Know you could tumble any second, then decide what to do with your time.”

Inflamed: Deep Medicine and the Anatomy of Injustice (indie link) by Rupa Marya and Raj Patel What the authors mean by “deep medicine” is health in the context of family, community, and interconnection with the web of life. As the authors observe, “the body is itself a kind of place—not a solid object but a terrain through which things pass, and in which they sometimes settle… To wonder why some things settle in some bodies and not in others is to begin to ask questions about power, injustice, and inequity.” This is an astute, illuminating, and necessary read.

Inciting Joy: Essays (indie link) by Ross Gay

This is exactly the book I needed on a sad day. It is tender and informed wisdom. Each section brims with bittersweet awareness of why joy is so necessary, even life-giving, among all that’s broken. In the first few pages I thought about getting highlighters to mark up the most memorable passages, but realized I’d be rainbowing the whole book. I may love the way the author writes but love even more his warm, witty, fiercely furious footnotes.

“Sharing what we love is dangerous,” Gay writes. “It is vulnerable, is like baring your neck, or your belly, and it reveals that, in some ways, we are all commonly tender.”

“It seems to me that grief is not gotten over, it is gotten into. And the griever teaches us, or reminds us, there is no pulling it together. There are only degrees or expressions of falling apart. Because grieving, alert to connection, luminous with it, is never only one person’s experience. In fact, I think it is the case that grieving, or the griever, consciously or not, connects to all of grief, and to all grievers, and which is perhaps why there are some traditions in which the griever is held in constant vigil for a long time—those traditions understand the griever is entering the oceanic sorrow, is drifting into it. And those traditions know, connected as we are, we are obligated to keep an eye on each other as the waters of grief close behind us.”

Rooted: Life at the Crossroads of Science, Nature, and Spirit (indie link) by Lyanda Lynn Haupt

This is an inspiring look at our inextricable connection to all of nature. Haupt winds threads of poetry, myth, and storytelling through the loom of multiple scientific disciplines in chapters with reader-focused titles such as “listen,” “wander,” “immerse,” “unsee,” and “create.” I’ve read a lot of similar works, yet truly appreciate the beautiful way this author pulls it together along with gently constructed reminders about what’s necessary and true. Here’s a glimpse of her work.

“We have come to an earthen moment wherein we must make all the connections we are able with the whole of life, no matter how at-risk that puts our public-facing façade of normality. Look at the vapid homogeneity of the wealth-based, earth-denuding, dominant culture: is this the approval we seek? When we turn to the sweet, ragged edges of society, we see the people carrying violins, mandolins, pens, microscopes, walking sticks. The ones with ink on their hands, paint on their faces, mosses in their hair, shirts on sideways because they have been awake all night in the thrall of a new idea. This is where the art of earth-saving lies. We are creating a new story –one of vitality, conviviality, feralness (escape!), wildness, nonduality, interconnectedness, generosity, sensuality, creativity, knowledge of the earth and all that dwells therein.”

Riding the Lightning: A Year in the Life of a New York City Paramedic (indie link) by Anthony Almojera

This straightforward and gripping memoir is by a first responder who had seen it all, until the pandemic hit. His account shares his own story as well as those of patients and coworkers. He writes, “I thought I could handle anything my job threw at me. That I could witness any amount of suffering. That I was someone people could lean on. After all, I was the senior paramedic, the man who could restart a person’s heart or detect a ruptured aneurysm… I was the union vice president, the one who blasted the higher-ups on Twitter and butted heads with them in person to defend my coworkers’ rights. I was also the guy who cooked a nine-course meal for his friends at Christmas and organized group vacations to Hong Kong and Dublin and Uganda. I thought I had all the answers.” This is quite a read.

Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative (indie link) by Melissa Febos.

Febos demonstrates the subversive power of self-reflection in a time when women’s narratives are still derided. The personal is indeed the political, not only for the benefit of the writer but for our culture.

The author writes, “Listen to me: It is not gauche to write about trauma. It is subversive. The stigma of victimhood is a timeworn tool of oppressive powers to gaslight the people they subjugate into believing that by naming their disempowerment they are being dramatic, whining, attention-grabbing, or else beating a dead horse. By convincing us to police our own and one another’s stories, they have enlisted us in the project of our own continued disempowerment.”

And this, which really begs to be cross-stitched and hung on walls. “I asked the clinician, ‘Is there therapy for women with Patriarchy? I’m asking for every friend I have.'”

Lost & Found (indie link) by Kathryn Schulz

A memoir as well as extended exploration into the meaning of loss and discovery. Schulz writes, “We live remarkable lives because life itself is remarkable, a fact that is impossible not to notice if only suffering leaves us alone for long enough.”

The author takes a piercing look at the paradoxes perplexing her. She notes, “One of them, akin to the feeling of losing something, is that the universe is dauntingly large and we are terrifyingly insignificant. The other, akin to the feeling of finding, is that the universe is dauntingly large and yet here we are, unimaginably unlikely and therefore precious beyond measure. As with so many other contrasting feelings, most of us will experience both of these eventually.”

Time to Create: Hands-On Explorations in Process Art for Young Children (indie link) by Christie Burnett.

I have a thing for process-oriented approaches to creativity, especially for kids. There are lots of inspiring books out there which, like this one, emphasize open-ended exploration of drawing, painting, printmaking, sculpture, and more — pushing back against the early ed as well as craft kit-based focus on cookie-cutter projects.

That Bird Has My Wings: The Autobiography of an Innocent Man on Death Row (indie link) by Jarvis Jay Masters

The Adverse Childhood Experiences scale couldn’t possibly rate the traumas this author endured from infancy on. Masters and his three siblings were severely neglected by drug-addicted parents. The children ended up in the foster care system, worse, they were separated from each other. For the first few years Masters lived with an elderly couple who guided him with kindness and love. Too soon he was tossed into a series of foster homes and institutional settings.

He does not forget to highlight the positives he experienced, rare moments of peace in the midst of turmoil. Once, a teacher in a youth correctional facility asked students to help move desks and chairs to the edge of the classroom. “Then he sat us all down in a circle, brought out his guitar, and sang songs. We recognized the lyrics—the poems and stories we ourselves had written! After that I wrote more, searching dictionaries for new words to express myself. Every day we walked out of class believing that what we did mattered.”

But eventually he turned in the direction of violence. He writes, “I began to appreciate myself more by breaking the rules. I was putting myself in charge of why I was not going home, so having no home didn’t hurt the way pain does when you have no control.”

Masters opens up to the study and practice of Buddhism, which changes his life. He still remains on death row for a crime he did not commit.

Did Ye Hear Mammy Died? A Memoir (indie link) by Séamas O’Reilly

Witty yet tender account of how a family goes on after a mother of 11 dies. The author is five years old when it happens. He writes their home is decked out for the wake with “folded chairs, industrial quantities of tea, and [an] expanding population of desolate mourners.” Being so young, O’Reilly didn’t understand “the solemnity, not to mention the permanence” of his mother’s death. So he went around the wake “appalling each person on their entry to the room by thrusting my beaming, 3-ft. frame in front of them like a chipper little maître’d, with the cheerful enquiry: ‘Did ye hear Mammy died?'”

The author’s father is not a man who accepts pity, although he is a singular character described as “God’s one, true, perfect miser.” This is a charming, often laugh-aloud account of how O’Reilly continues to have a childhood. As he explains, “I’d laugh and cry and scream about borrowed jumpers, school fights, bomb scares, playing Zelda, teenage bands, primary-school crushes…I’d just be doing it without her.”

The Angel and the Assassin: The Tiny Brain Cell That Changed the Course of Medicine (indie link) by Donna Jackson Nakazawa

Thanks to insomnia, I read a good pile of books each week. I stayed up nearly all night to finish Nakazawa’s revolutionary & relevant-to-everyone The Angel and the Assassin. Suggestion –you’ll want a highlighter and post-its. Here are two tidbits:

“The higher an individual’s levels of inflammatory biomarkers, the more prevalent their psychiatric symptoms tend to be… This turns out to be true even when no signs of physical illness or inflammation are detected.”

“Whatever term we use to refer to these brain changes, they all mean the same thing: Tiny microglia are engulfing and destroying synapses, and this is the catalyst that sets in motion hundreds of different disorders and diseases that have long remained the black box of psychiatry and neurology. This means that the long-held line in the sand between mental and physical health simply does not exist. When an individual’s immune system is overtaxed, for some, disease may show up in the brain, while for others it may show up in the body. It could inflame your joints, or your mind — or both.”

The author shares information about possible treatments to restore the activity of our brain’s immune reaction, moving from over or under-reaction to a healthy mean. This has profound implications for dementia, depression, and many other conditions resistant to treatment.

My only criticism is I wish the author had used a less gee-whiz tone when writing about these potential cures and had stepped well away from the proprietary side of the fast-mimicking diet, but these are minor issues for a huge wow of a book.

Slow Stitch: Mindful and Contemplative Textile Art (indie link) Claire Wellesley-Smith

I love all kinds of art-making— street art, found art, textile art, outsider art, repurposed anything. Books like this one help me dream of doing more innovative sewing. The author wends her own thoughts along as she shares work from individual and community projects that beautifully transcend how-to’s, patterns, and rules.

The Nature of Nature: Why We Need the Wild (indie link) by Enric Sala

The author, director of National Geographic’s Pristine Seas project (which has succeeded in protecting more than 5 million sq km of ocean), writes about his transition from academia to activism. He writes, “A degraded environment is a hotbed of all the problems affecting humanity” and clearly explains how saving nature saves us all, whether the topic is feeding the world, preventing the next pandemic, or halting climate change. As he says, “We are in the midst of an existential crisis, not only affecting the survival of our very society, but also about our place in the world.”

&&&

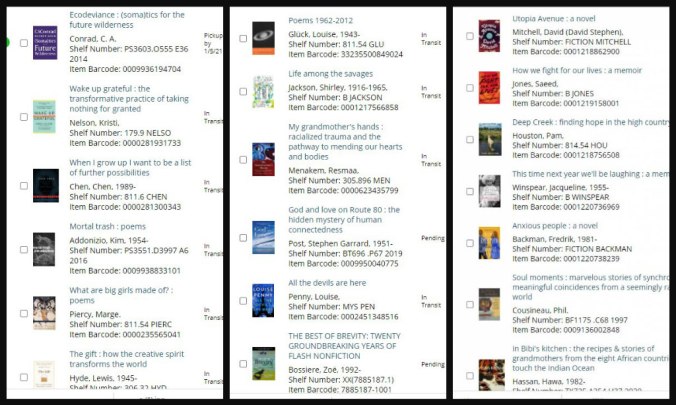

This is just a sample of favorite reads from 2022, a small-ish sample based on the 207 books read this year. I keep track of my reading diet on Goodreads, mostly to keep myself from starting a book I’ve already read but also to give stars to authors who always benefit from positive reader feedback. I’m not good at plugging my own books but they, too, are hungry for readers.

Here are my recent favorites lists:

Favorite 2021 Reads (if you can tolerate the unfixably bad format of this post)

I’d love to hear about your favorites in the comments. And happy reading!

Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Futures

Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Futures The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair With Nature

The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair With Nature See No Stranger: A Memoir and Manifesto of Revolutionary Love

See No Stranger: A Memoir and Manifesto of Revolutionary Love  To Speak for the Trees: My Life’s Journey from Ancient Celtic Wisdom to a Healing Vision of the

To Speak for the Trees: My Life’s Journey from Ancient Celtic Wisdom to a Healing Vision of the Field of Compassion: How the New Cosmology is Transforming Spiritual Life

Field of Compassion: How the New Cosmology is Transforming Spiritual Life

Thin Places: Essays from In Between

Thin Places: Essays from In Between  The Oldest Story In The World

The Oldest Story In The World Becoming Duchess Goldblatt

Becoming Duchess Goldblatt  The Overstory

The Overstory  Sharks in the Time of Saviors

Sharks in the Time of Saviors

Hamnet

Hamnet

The Night Watchman

The Night Watchman

Betty

Betty The Boy in the Field

The Boy in the Field Stars of Alabama

Stars of Alabama