I got my first summer job when I was 13 years old. My official title was “feeder.” This was my first exposure to time clocks and posted schedules. Also my first exposure to quite a bit more.

My grandparents had died a few years earlier after protracted illnesses, and like many others, I associated the sounds and smells of the unhealthy elderly with my own grief.

Before I started all I knew was that was supposed to wear a white uniform to work. On my first day I was informed my only task was to spoon-feed patients unable to feed themselves. The head nurse handed me a list of names with room numbers and told me I had to be done in two hours. “It doesn’t matter if you clock out late,” she said, “We aren’t paying you more than your allotted two hours.” Her swiftly delivered instructions were entirely lacking in useful information.

As I walked down the hall I discovered every resident there thought I was a nurse. Me, a girl who fell over her own feet. Me, a girl who could barely endure the sorrow of driving past a puppy chained to a tree, an unknown puppy whose imagined plight kept me upset for hours. Now I was surrounded by real plight.

Perilously frail people lined the hallway. Nearly every one of them sought my attention. They asked me to get them something urgent like a bedpan or a pill. They asked why they couldn’t go home or lie down or find something missing. They asked to simply to engage in a little conversation. I was overwhelmed.

One woman cried as she begged me to hold her hand. I smiled and nodded. As I listened to her cry I couldn’t help but steal glances at her hand’s bumpy joints and raised purple veins. I realized it had once been as strong and soft as mine. Time’s appetite made me feel as if the walls, floors, and ceiling were already collapsing. But I had a job to perform. Surely hungry people were waiting for me. She wouldn’t let go. Not knowing what else to do, I crouched by her wheelchair there in the hallway and smiled weakly as I carefully uncurled her fingers from mine.

The patients I was expected to feed lay hostage on narrow beds in identical rooms. Each person’s eyes stared, some directly at me and some at a place well beyond me. Trays of pureed food waited at each bedside. I had to figure out how to lower the metal bed rails in order to reach patients. I held out wavering spoonfuls of meat, potatoes, and vegetables pureed into of a nauseating mush of pale browns and olive greens. After the first patient gagged, I realized it was possible to raise a person’s head and shoulders using a crank at the foot of the bed. Like every other surface, those crank handles seemed to bristle with germs.

I was repulsed by almost everything there except for the people. I found their faces especially compelling. One of the few men on my list was hunched and fierce like a hawk, giving the impression he was ready to fly at any moment. One woman’s deep-set brown eyes were beseeching although she could say only a few garbled words. She looked at me as if she could see much more than those who walk and talk so casually could do. Another woman, whose powdery thin skin and soft clouds of white hair made her look angelic, rarely opened her eyes. When she did I felt strangely blessed. Her awake moments, although silent, felt like moments of expansive awareness.

Maybe it was a 13-year-old’s sense of drama, but I loved these people in a way I couldn’t explain. I wanted them to feel comfort and peace in the minutes we had together. I didn’t know how to accomplish that. But I started, from my first day, to ask them a question. I told them my name each time, that I was there with dinner, and then I asked them what they’d like me to know or asked what it was like to be them. And then I was quiet while I listened to whatever their silence could tell me. I knew most couldn’t hear me or answer me. But I was sure there was a reason I felt something different in the presence of each person. I felt it strongly.

Sometimes an aide would hustle into the room and sharply tell me to hurry. “No use talking to someone stone deaf” or “Ain’t nobody home in there.” But somehow these people, not fully in the stream of life and yet not departed, seemed imbued with more instead of less. They were my elders, far ahead of me in every way, and I hoped for a hint of what they knew. I wished to make my attention into an antennae to pick up whatever they might be sending.

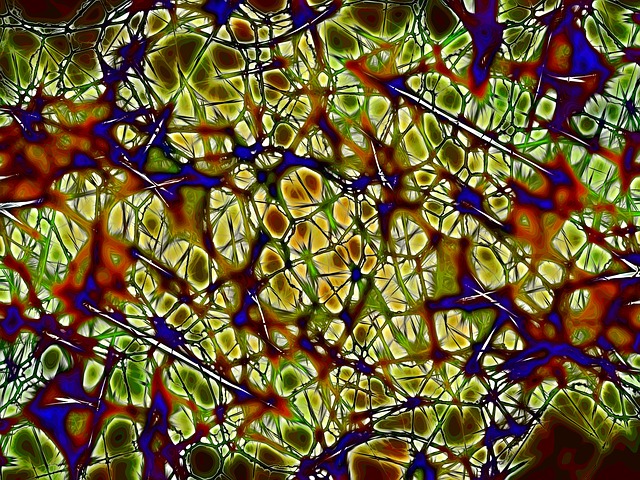

This is a way of communication I have continued to explore. We humans are connected by much more than language and social norms. We understand each other in far less overt ways. We entrain to one another’s heartbeats, synchronize our moods, react to the light each living cell emits, and pick up energy that some call intuition and others call morphic resonance.

It wasn’t anything I talked about then and even now it’s hard to explain. This is hardly a process unique to me, just something I am still trying learn. If I had to put it in steps, here they are.

1. Pay close attention to the other person. You may choose to look at them for as long as is comfortable, or simply to sit quietly nearby.

2. Be aware of your bodily sensations. Recognize them without making a mental effort to interpret them, at least right away. They are significant.

3. Be aware of seemingly irrelevant things that occur to you—song lyrics, flickering memories, a rush of emotion. Recognize these without making an effort to interpret them. These too are significant.

4. Slow down, staying with your awareness of the present moment. You are allowing your heart’s wisdom to enter your consciousness. Opening to understanding with your most vulnerable self, unguarded by the analytical mind, can be a way to receive such wisdom.

5. Send kindness to the other person in whatever way you can. perhaps as a quiet blanket of compassion or as waves of love. Your heart’s electrical impulse emanates several feet from your body, affecting the electrical impulse of another person’s heart within that distance. A loving heart actually transmits that sensation to people nearby. The kindness you send is received. Trust that.

6. After following this procedure through several visits you may choose to send a request from the deepest part of yourself to the other person. Then pay attention to the sensations in your own body, to whatever images and emotions arise, and to the quiet sense of knowing that seems to come from nowhere. These are a response. You may have to work hard to refrain from inserting what you think into the situation. Stay centered.

7. Honor the other person. Choose to close with a prayer, a kiss, a few minutes to rub lotion on his or her hands, or some other direct contact.

My summer as a Feeder seemed endless. I wasn’t good at my job. I realize now how badly informed I was in my position. Not only was I not instructed to raise the head of the bed, I also wasn’t told how much to feed each person or how important it was to get them to drink. I remember feeding very little to the people who looked away, closing their mouths against nourishment. I didn’t know what else to do for people who were trapped in small sweltering rooms inside barely functioning bodies. I could hardly eat that summer either. The smell of the nursing home—old urine and cooked cabbage—seemed to reappear in my nostrils at odd moments, leaving me with no appetite.

After my work was finished each afternoon I spent time listening to the patients parked in wheelchairs and those walking along the hallway handrails. They told me of tragedies. Not the wars and poverty they’d experienced but more recent sorrows— children who didn’t visit, pets gone, choices taken away. They begged me to help them in dozens of ways, every one beyond my ability. They cried. Several women there were healthy in body and mind, but had lost their homes and possessions when they recovered from supposedly terminal conditions, leaving them in institutionalized for years. One man, Joe, told me every day that he was afraid of burning in hell. He insisted he was doomed for eternity unless he could confess to a priest. With the hubris of a non-Catholic, I thought I could easily fix the problem. I told him I’d get someone to come from the Catholic church a half mile away. When I called I was told no priest would come, as a layperson conducted all required nursing home ministry tasks. The next day I asked Joe if he would confess to a layperson. He shook his head with sorrow so profound I could barely breathe.

My job was over when school started. I promised myself I would go back to visit. The faces of the people I fed rose up in my idle moments and in my dreams, but I didn’t go back. The silences I held for them became my own silence.

What if a man cannot be made to say anything?

How do you learn his hidden nature?

…I sit in front of him in silence,

and set up a ladder made of patience,

and if in his presence a language from beyond joy

and beyond grief begins to pour from my chest,

I know that his soul is as deep and bright

as the start Canopus rising over Yemen.

…there’s a window open between us,

mixing the night air of our beings.

Rumi